Someone once said that “the only works of art America had contributed to the world were her plumbing and her bridges”.

Somewhere in a Chinese factory, an American made urinal is broken.

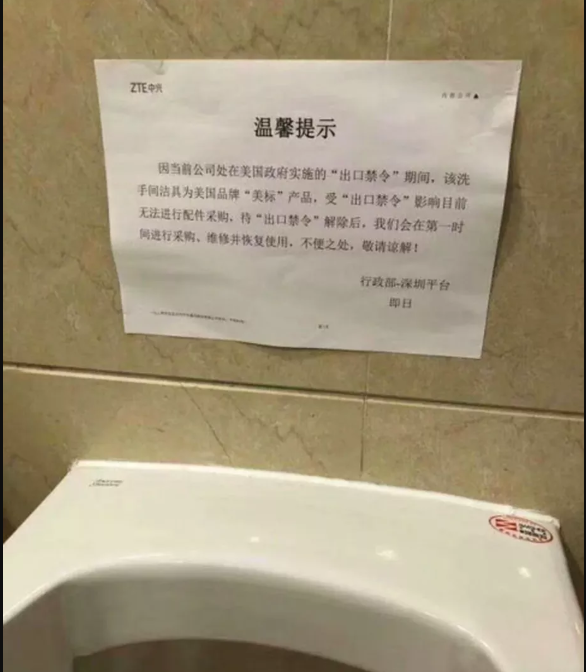

A photo shared on the Chinese microblogging site Weibo, probably taken by a panicking, cross legged, low level employee, shows a note above the offending urinal, saying that it cannot be fixed without ordering parts from the US, which would violate recent sanctions.

“Our company is now subject to the export ban posed by the US government. Since this bathroom appliance is a product of American Standard, we can’t procure the spare parts for repair due to the export ban,” the note, which journalists verified with an ZTE employee as authentic, reads. “When the export ban is lifted, we promise to get the parts, repair it, and resume operation at once. We regret any inconvenience this may have caused.”

When one thinks of American Standard, Corona, Armitage Shanks, Ideal or Kohler, ceramic giants that they might well be, one can’t help of course but think of the one brand missing from the latest offering by Rotolux Press, i.e. J.L. Mott, the firm responsible for manufacturing that one urinal which changed the course of art, and perhaps the world, forever.

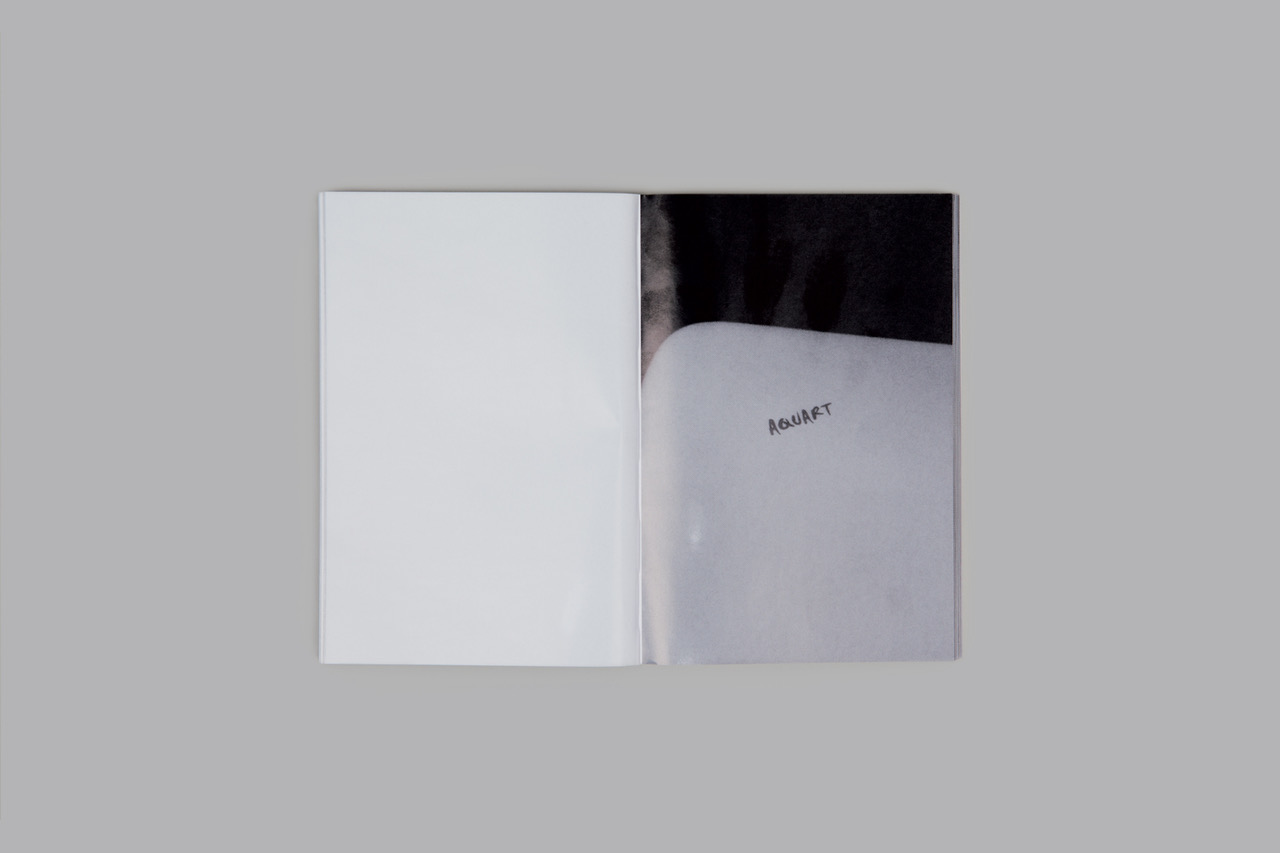

A pocketbook. A silvery metallic cover hiding a substantial collection of black and white photos where cisterns, cuvettes, bowls and tanks provide the backdrop for logotypes and brandnames, each one the result of hours of work of different graphic designers, from thinking, to drawing, to screen work, through endless meetings and prototypes, before that final stamp of smooth white approval.

A scrap book for piss artists, a pile of souvenirs in alphabetical order, and the odd stray pubic hair, my own favorite comes around twelve photos in, with a very clear image of the Aquart logo, looking like its creator simply drew it, albeit carefully, onto the white surface using a sharpie. Two pages later, the uneven logo of the aforementioned Armitage Shanks also seems to have been jotted directly onto the background by a particularly careful and attentive vandal.

What Beatrice Wood wrote about Duchamp could equally be applied here, namely, “Whether Mr [Garnier] with his own hands made the [logo] or not has no importance. He CHOSE it. He took an ordinary article of life, placed it so that its useful significance disappeared under the new title and point of view – created a new thought for that object.”

The furtive glimpse of Garnier that we are given as he catches himself photographing the Toto logo reminded me of a recent trip back home to Dublin for a few days with a buddy – a city that might well be a mecca for toilet lovers all around the world when one considers the massive number of public houses that it contains, which by the very nature of their business model, generate the constant and sometimes violent need to urinate. Our visit is something that will eventually become transformed into a kind of rite, or ritual, a repetitive return to the same, at least similar, form.

We had settled into a tiny but very familiar pub that sits right on the edge of an isolated bay on the city’s northern coast.

After a couple of hours spent in the beer soaked wooden hut of the bar area and in the middle of a particularly creamy third pint, the proverbial penny had to be spent. Wandering through the Thursday night crowd towards the men’s toilets, I held my breath as I turned a corner into the cramped space and was taken aback by the sight of a brand new, pink, pinstriped shirt and a brown leather belt hanging from a tap at the top of a particularly ornate central ceramic and marble arched urinal. No cabinets, just one wall lined with the barest steel trough, another with three stainless steel sinks, and at the end of the room, on the back wall, sitting between the two, that fantastic series of marble arches, almost one meter sixty in height, with their elegant embedded chrome pipework crowning the ensemble.

Almost religiously, one has to mount a burgundy tiled step to gain access.

Sidling around the clean, quite newish, shirt and belt, and stepping up I relieved myself against the stoic and robustly named Adamant urinal.

Having finished, I negligently washed my hands and then took the long route back to my barstool and the continuation of the conversation with my friend. What has to happen in a public toilet that requires someone taking off their shirt and belt? What made them leave so hurriedly that they left them behind?

I pushed and struggled through the crowds in the pub, eyes peeled, on the look out for shirtless punters who might provide some explanation for the toilet scene.

I saw five in the crowd that night.

All men.

Four of them still had their belts on.

The fifth was wearing running shorts.

“The J.L. Mott Iron Works” is edited, designed and published by Rotolux Press, with images by Alaric Garnier.