The lecture transcribed on the following pages critical political â Hans-Rudolf Lutz (1939-1998): Swiss typographer, author, designer, publisher, collector, visual director and teacher took place during the Leipzig Book Fair, for which Switzerland was the guest country. Mirjam Fischer and Eveline WĂŒthrich organized the lecturing programme Rules & Schools on the 15th of March 2014 at the Hochschule for Graphic Design and Book Art of Leipzig.

Sebastian Cremers & Tania Prill

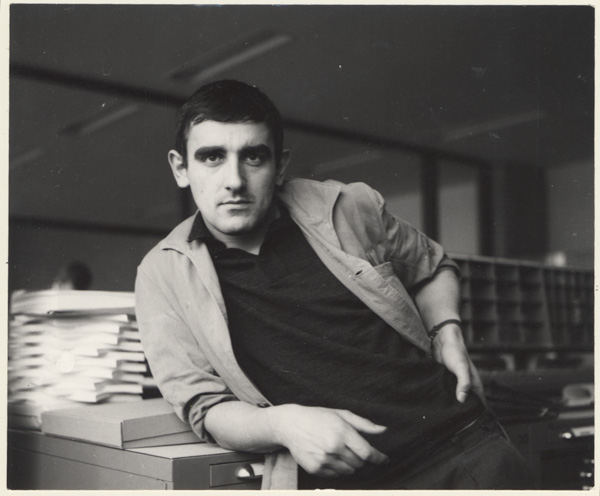

Hans-Rudolf Lutz

Hans-Rudolf Lutz began his apprenticeship as typesetter in the long-standing company of Orell FĂŒssli in ZĂŒrich in 1955. This professional orientation was coincidental and he considered his working days as being monotonous.

Lutz writes the following about this period: âI was cheeky and was almost thrown out a few times. At that time though, you didnât need much to get into a clinch with the boss. But they actually wanted to forbid me wearing jeans and my trendy Elvis hairdo!â

In search of models in design he soon discovered the representatives of âSwiss Graphic Designâ, the overheard term of âfunctionalityâ means âtotal reduction of the design meansâ to him.

Before that, Lutz had cut his way through a four-year apprenticeship in typesetting and only survived all this time because he knew that afterwards, he would be able to go on âa long tripâ. He hitchhiked towards the North Cape. The three months he had planned turned into more than two years. He earned his living by doing cleaning in Stockholm, fine-drawing in Helsinki, typesetting in Tunis, and as a sailor and cook assistant on different freight ships. This journey âbroke down my creative dogmatism. I realized that intuition and systematization do not necessarily exclude each other.â

In 1963 Lutz began his one-year course on typographic design with Emil Ruder and Robert BĂŒchler at the vocational school in Basel. In fact, this course did not really exist, everything was improvised â very unswissly. Emil Ruder and Robert BĂŒchler sacrificed their breaks in order to discuss the works and this was the first time that Lutz could concern himself with typographic design on a full time basis. In spite of all the criticism to Emil Ruder, Lutz appreciated his implacable eye for design inconsistency.

In 1964, Lutz became the leader of the group âexpression typographiqueâ in the studio Hollenstein in Paris in order to explore and propagate the potentials of filmsetting. In 1966 he accepts a position as teacher of typography and interdisciplinary design in Lucerne. He participated at the creation of the F&F: School for experimental design in ZĂŒrich. As of 1966, Lutz led his own studio in ZĂŒrich. In the same year, he created the publishing house Hans-Rudolf Lutz.

With a book series 3 years later, Lutz breached the 15-year boycott against the Marxist art theorist, Konrad Farner.

He became member of the music group UnknownMiX as their visual director in 1983.

Hans-Rudolf Lutz died in February 1998.

âWieviel Erde braucht der Mensch?â, 1971

Actor: Hans-Rudolf Lutz

Direction: Alex Sadkowsky

Production, camera, editing: Hans R. Bossert

Hello,

Puddle

Tania Prill and I will introduce to you the Swiss typographer, designer, author, publisher, visual director and teacher Hans-Rudolf Lutz.

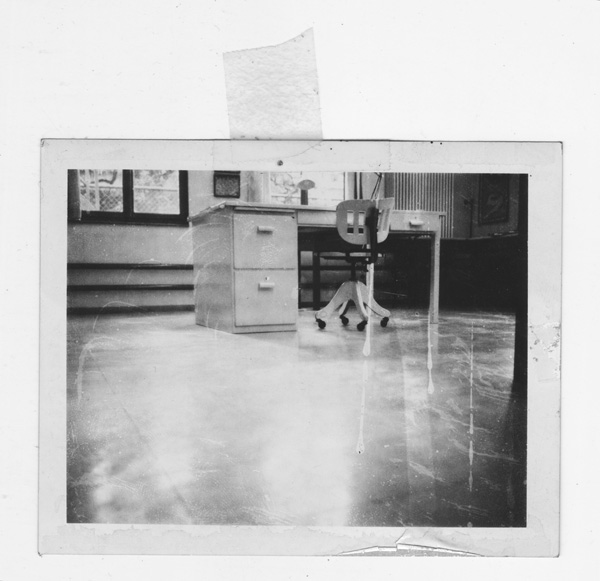

Together with Alberto Vieceli, we work in Hans-Rudolf Lutzâs former workshop in the Lessingstrasse in ZĂŒrich.

Tania was married to Hans-Rudolf Lutz. She administrates his bequeath and manages the publishing house Hans-Rudolf Lutz.

I am also here as a publisher.

Hans-Rudolf Lutz’s workshop

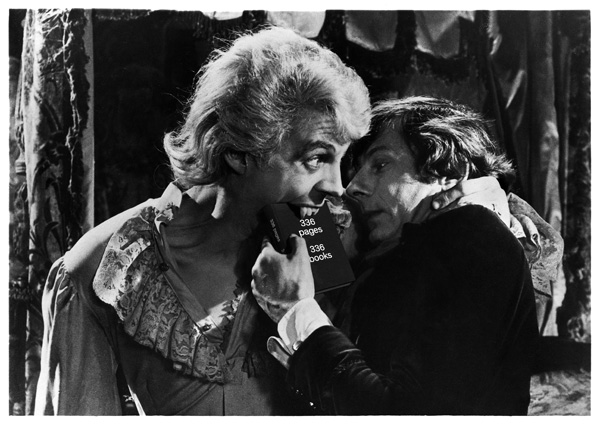

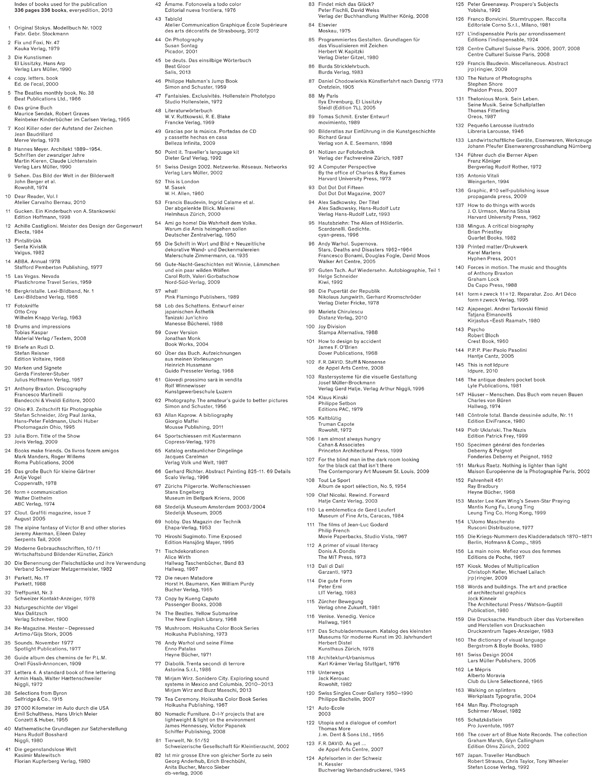

Half a year ago I initiated âeveryeditionâ and would like to present this new edition of the publication âThe Miami Heraldâ by Hans-Rudolf Lutz, revised by Tania and myself, as well as the book â336 pages 336 booksâ by Tania, Alberto and me which reveals ties with Hans-Rudolf Lutzâs work, as well as to books as such.

On the basis of several projects, we will show you how Hans-Rudolf Lutz worked. We especially focus on the manifold interconnections between word and picture in his work. Furthermore we would like to confront some of his works with projects that emerged independently from Lutz and created a contentual tie that can widen the angle of view.

These correlations will also play a role in the exhibition on Hans-Rudolf Lutz that we are currently working on.

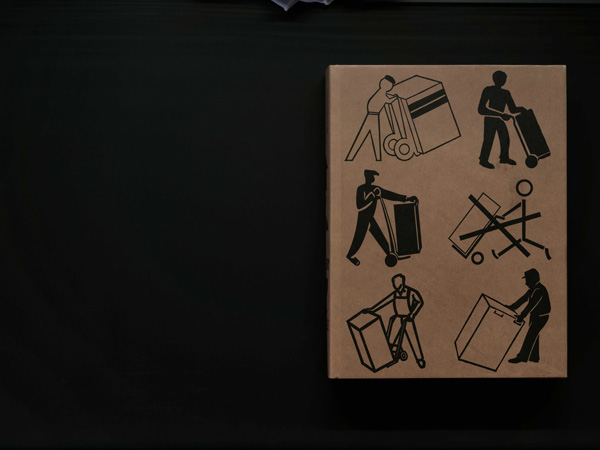

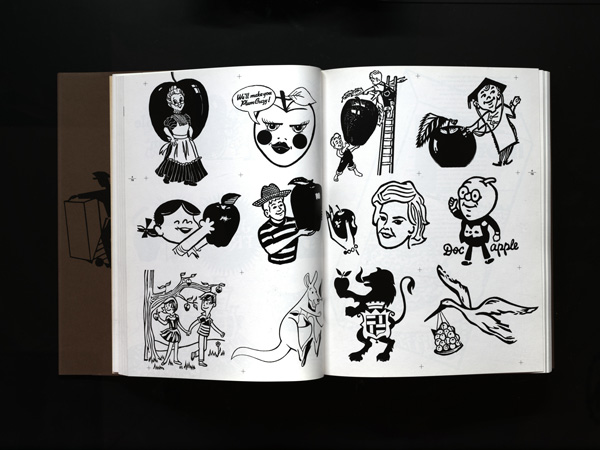

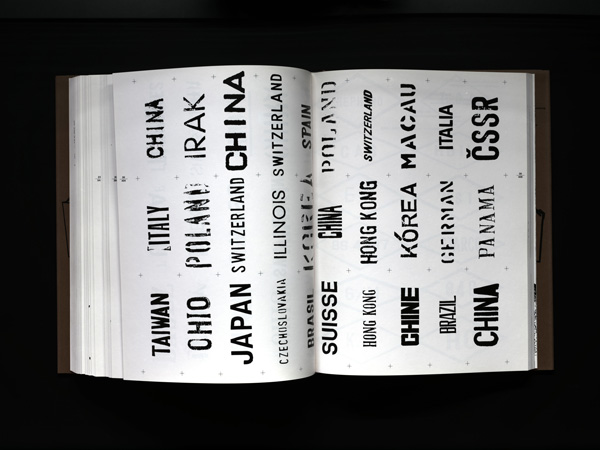

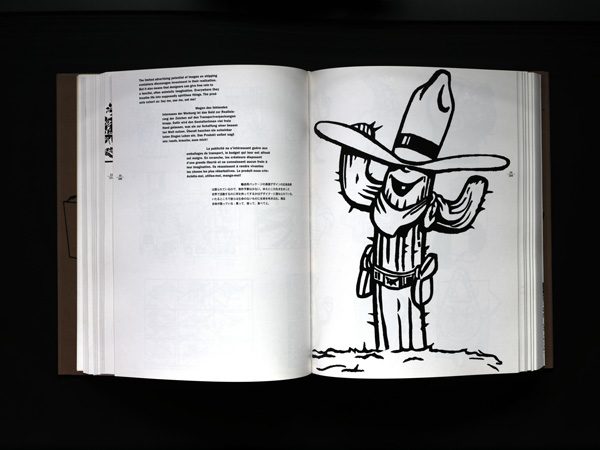

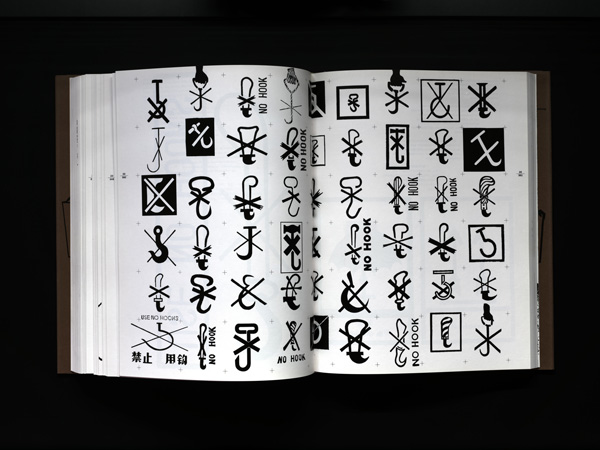

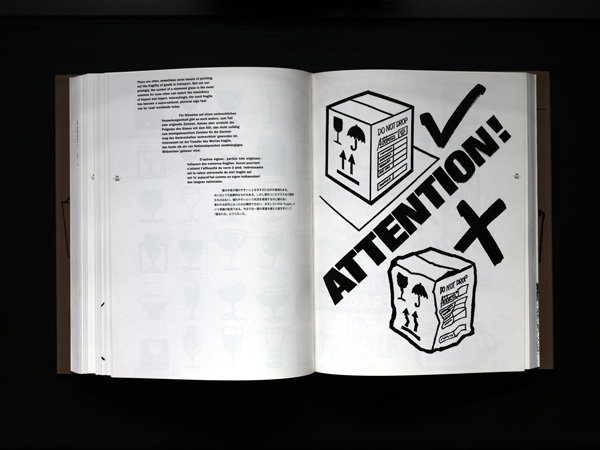

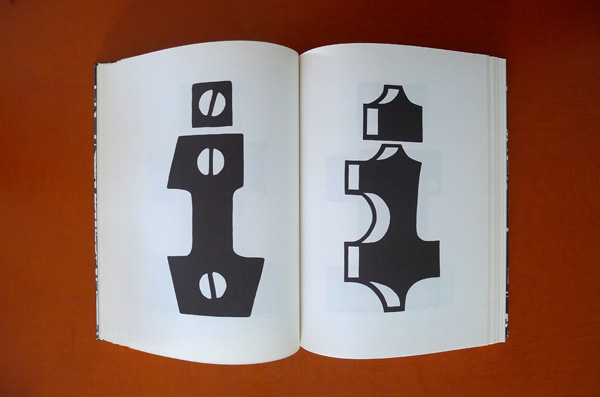

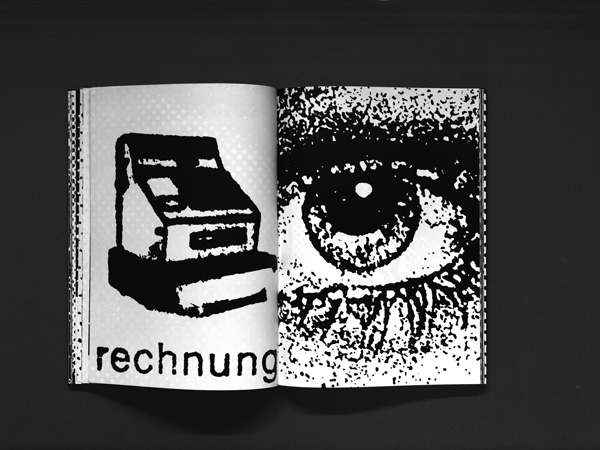

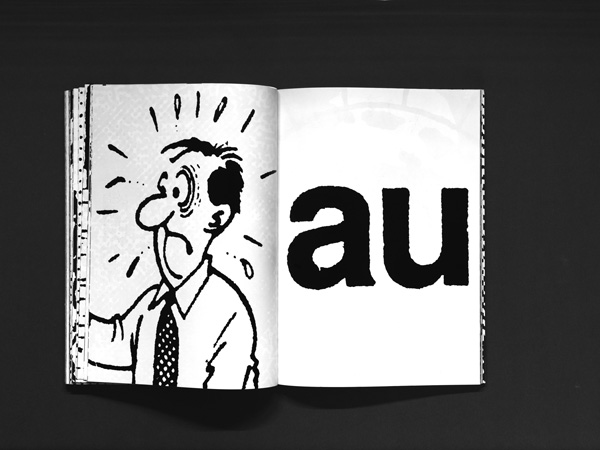

âTodayâs Hieroglyphsâ

Hans-Rudolf Lutz’s collection of signs

Hans-Rudolf Lutz describes the project as follows:

âFor 15 years I have been digging in trash piles of this world and end up promoting 15,000 of these visual treasures to be seen.â

Here you see a part of his collection that Lutz transformed in the repro-machine of the school in Lucerne SW.

5,000 of these signs were included in this book.

âTodayâs Hieroglyphsâ

Hans-Rudolf Lutz

528 pages, 22 x 29,4 cm

Verlag Hans-Rudolf Lutz, 1990

âTodayâs Hieroglyphsâ

Hans-Rudolf Lutz

528 pages, 22 x 29,4 cm

Verlag Hans-Rudolf Lutz, 1990

âTodayâs Hieroglyphsâ

Hans-Rudolf Lutz

528 pages, 22 x 29,4 cm

Verlag Hans-Rudolf Lutz, 1990

âTodayâs Hieroglyphsâ

Hans-Rudolf Lutz

528 pages, 22 x 29,4 cm

Verlag Hans-Rudolf Lutz, 1990

âTodayâs Hieroglyphsâ

Hans-Rudolf Lutz

528 pages, 22 x 29,4 cm

Verlag Hans-Rudolf Lutz, 1990

âTodayâs Hieroglyphsâ

Hans-Rudolf Lutz

528 pages, 22 x 29,4 cm

Verlag Hans-Rudolf Lutz, 1990

âTodayâs Hieroglyphsâ

Hans-Rudolf Lutz

528 pages, 22 x 29,4 cm

Verlag Hans-Rudolf Lutz, 1990

âTodayâs Hieroglyphsâ

Hans-Rudolf Lutz

528 pages, 22 x 29,4 cm

Verlag Hans-Rudolf Lutz, 1990

The signs on the corrugated cardboard packaging for transport are signs made by workers for workers.

Workmen and workwomen with only little design education allow these signs to keep a great pictorial value. Hans-Rudolf Lutz dedicated his book to them.

In spite of the reduction to the essentials, they are capable of introducing sensitivity, surprise and also a high informational value in their signs.

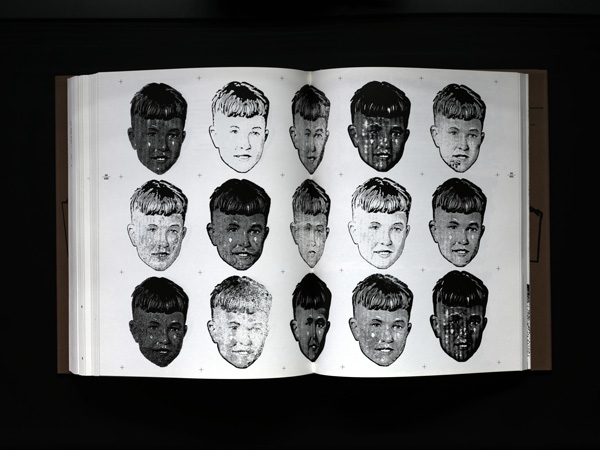

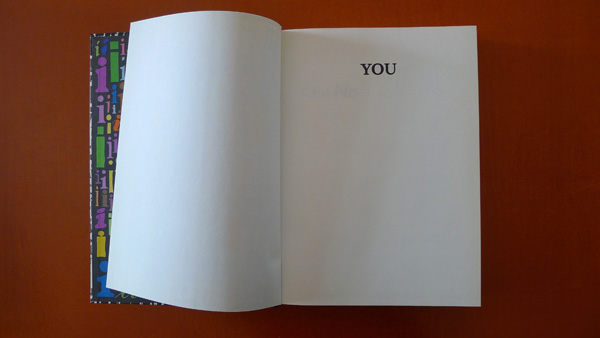

âYOU â 405 (406)â, Ann NoĂ«l

âYou â 405 (406)â

Ann Noël

Edition of 130 copies

published by Rainer Verlag Berlin, 1982

As a first correlation to âTodayâs Hieroglyphsâ, we will show you the artists book âYOU â 405(406)â by Ann NoĂ«l, published in 1982 in an edition of 130 copies. The artist lives and works in Berlin and was active in the Fluxus movement.

The book refers to the Me-Generation in the 70âs in the USA. Ann NoĂ«l lived in the States at the time.

âYou â 405 (406)â

Ann Noël

Edition of 130 copies

published by Rainer Verlag Berlin, 1982

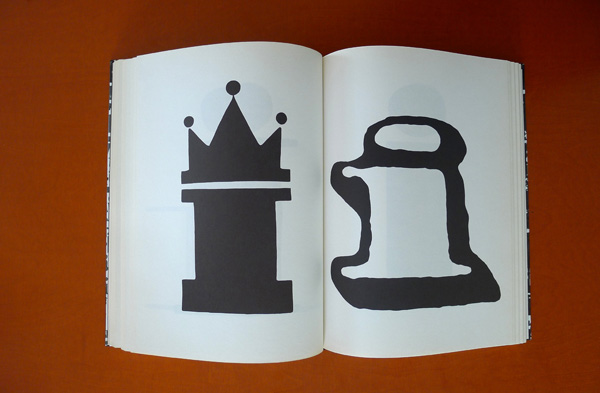

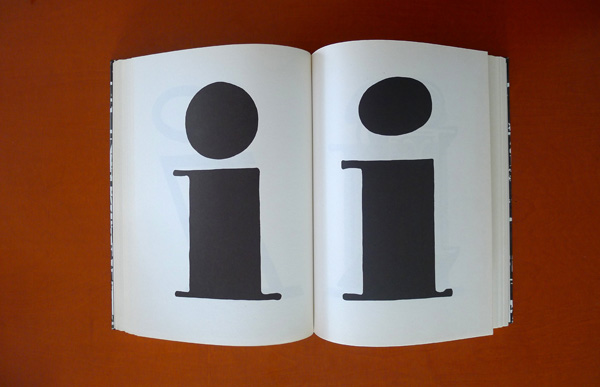

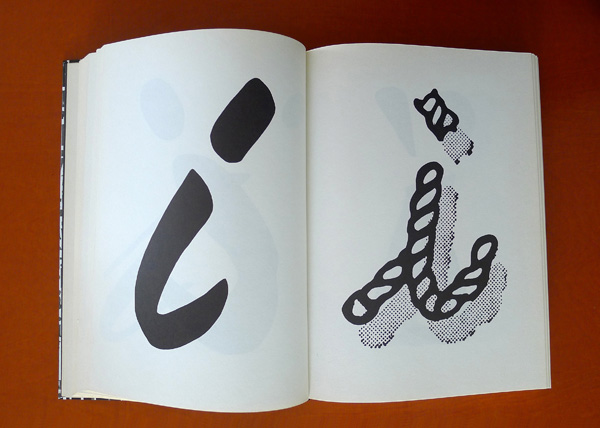

Whereas Hans-Rudolf Lutz shows the design diversity of âunprofessionalâ workmen and workwomen in his book âTodayâs Hieroglyphsâ, the exciting thing about this correlation is

âYou â 405 (406)â

Ann Noël

Edition of 130 copies

published by Rainer Verlag Berlin, 1982

that Ann NoĂ«lâs concern in her book is the expressive diversity of one artist, namely of her own person.

âYou â 405 (406)â

Ann Noël

Edition of 130 copies

published by Rainer Verlag Berlin, 1982

For this purpose she limited herself to one letter that also mutates to an image or rather a hieroglyph through its 405 variants.

âYou â 405 (406)â

Ann Noël

Edition of 130 copies

published by Rainer Verlag Berlin, 1982

âYou â 405 (406)â

Ann Noël

Edition of 130 copies

published by Rainer Verlag Berlin, 1982

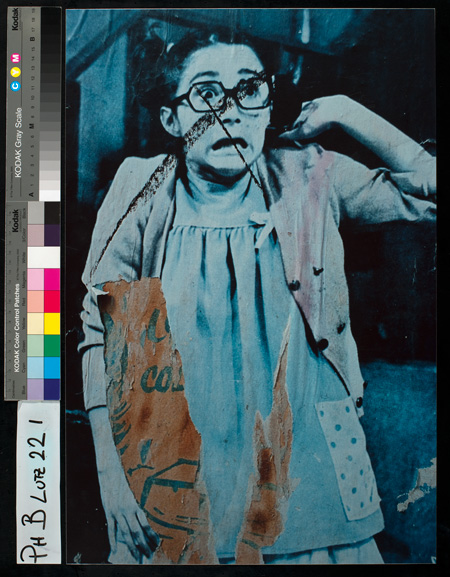

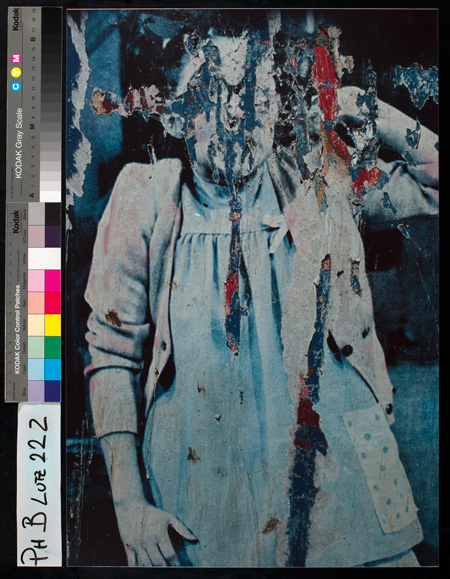

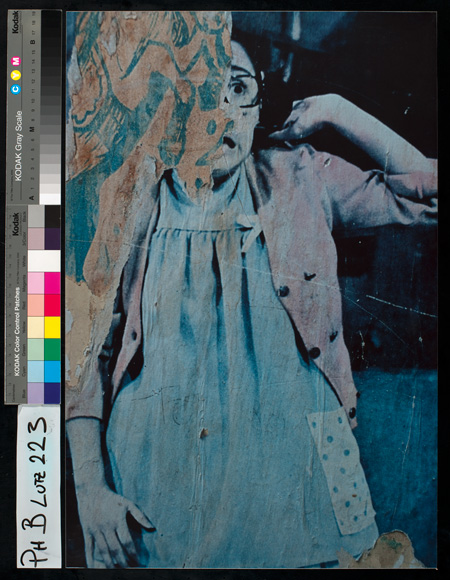

âDie Fixierung auf einen Zustand ist immer nur vorlĂ€ufigâ

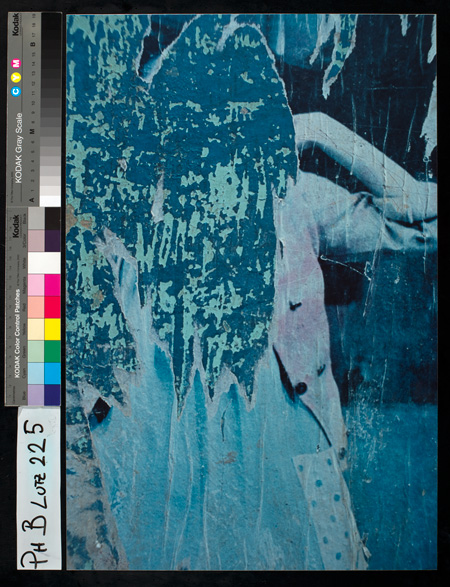

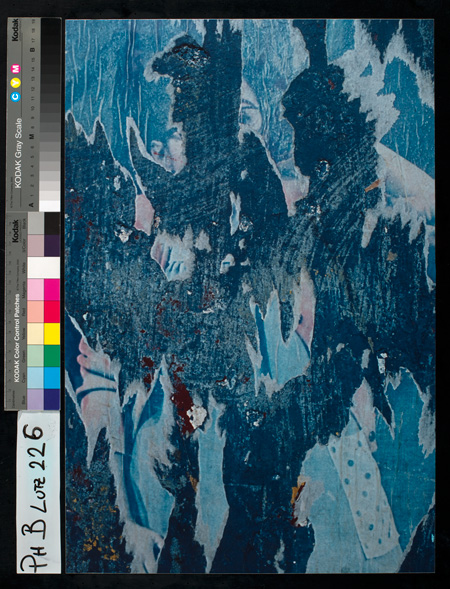

With the following series, Hans-Rudolf Lutz wanted to show that the designing process is not completed, when for example a poster has gone through the printing machine.

Quotation:

âFixation on one state is always just temporary. This knowledge relativises the meaning of our work, without making it insignificant or arbitrary.

Typographic design unifies just as much the permanent âcreation of orderâ as the âliking of disorderlinessâ. What is fascinating is that this is not contradictory.

Exposure e.g. to nature (sun, rain, wind, decay) and to people by scratching, scribbling, tearing off, drawing over and commenting transforms a series of the same to a series of changing ones.â

âDie Fixierung auf einen Zustand ist immer nur vorlĂ€ufigâ

âDie Fixierung auf einen Zustand ist immer nur vorlĂ€ufigâ

âDie Fixierung auf einen Zustand ist immer nur vorlĂ€ufigâ

âDie Fixierung auf einen Zustand ist immer nur vorlĂ€ufigâ

âDie Fixierung auf einen Zustand ist immer nur vorlĂ€ufigâ

âDie Fixierung auf einen Zustand ist immer nur vorlĂ€ufigâ

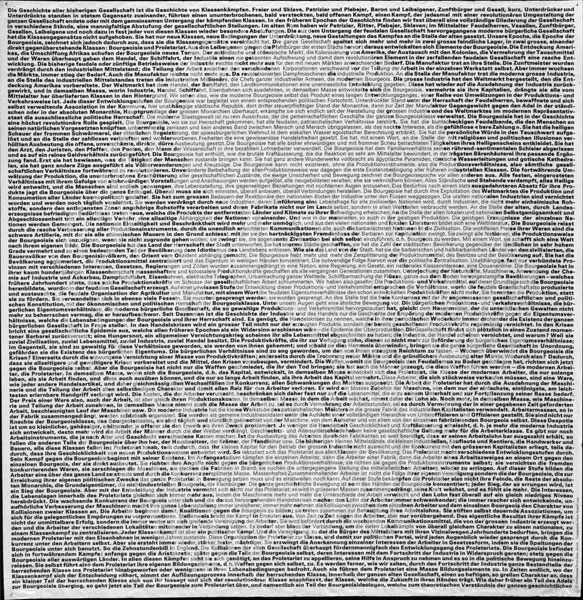

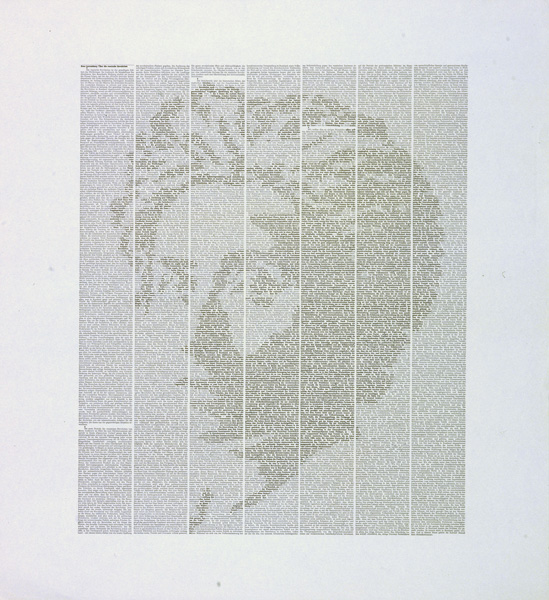

Writing > grid > picture > portrait of Karl Marx

âWriting > grid > picture > portrait of Karl Marxâ

In the 1960s Lutz was inspired by Wittgenstein to use language as a virtual material and thus open it to meanings. A continuation of this idea is the work âWriting > grid > picture > portrait of Karl Marxâ. Lutz comments it: âEven if we have got used to the separation of text and pictorial information, we could make the border between them more permeable.â

With the statement following a short introduction, âThe history of all previous societies has been the history of class strugglesâ Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels begin the first chapter of the Manifesto of the communist party.

Johannes Gachnang, artist, curator and publisher comments this in an interview with Jean Widmer in 2000: ââTypography is politicalâ â somehow that was already true. We too, were once young communists and this or that. At some point in time, we were always excluded, because of Trotzkist activities, Maoist activities, we were simply anarchists. Lutzâs poster revealing Marx through the type face of the communist manifesto is an attempt to visualize something. The text and the person are blended together in a very naive way. When you take into account the countless copies of this: a master stroke.â

âWriting > grid > picture > portrait of Karl Marxâ

Socialist graphic design is one of Lutzâs sources of inspiration. (âŠ) He endeavoured to keep his own strict canon in movement through imports and departures.

How can Protestantism be loosened in visual communication and saved over time? Not just any good form can save mankind, but rather renewal. It is not a concern about style, but about coordinates. When Lutz wanted to cooperate with advertisers, he was branded as a traitor.

I think Lutz was very serious in his attempt to deal with the given material. (âŠ) He constantly researched on how you can bring a text or a context or an idea into the picture.

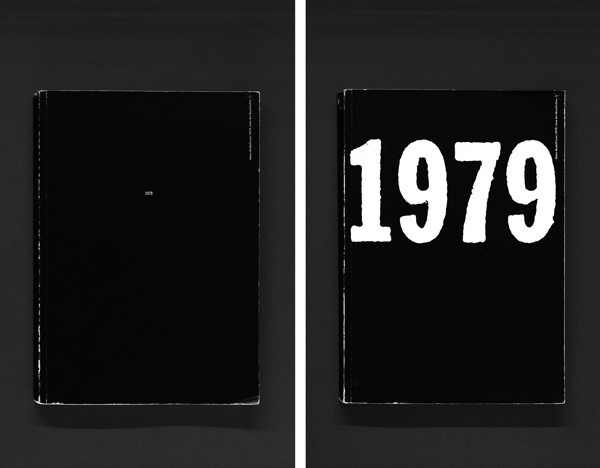

1979

1979 by Hans-Rudolf Lutz is an experimental proposal in this direction.

Fritz Billeter says to this project: âNo other media reports just as well the great and the petty world history all mixed as the daily newspaper. History books? They separate history from the here and now of our everyday life. More sensitive and instructive forms of history writing would induce much more of an active discussion about it, and this on rational and an emotional level. (…)â

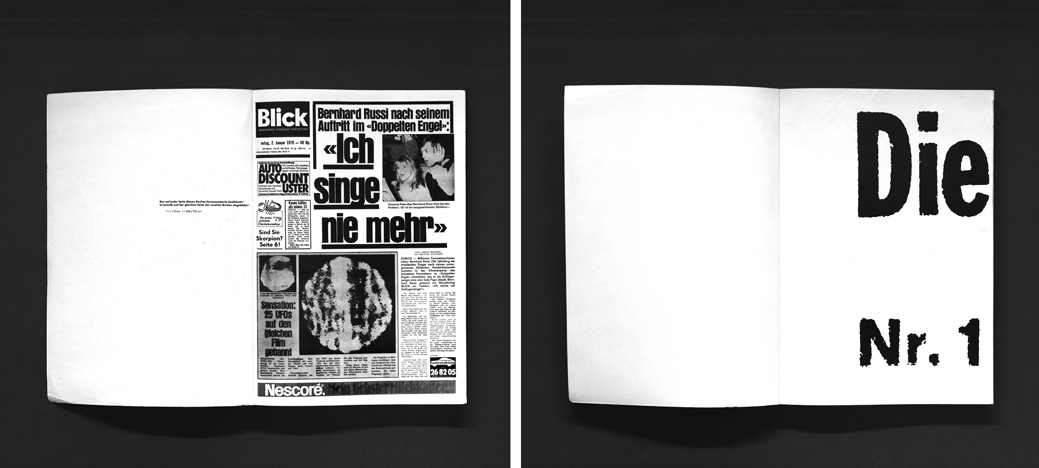

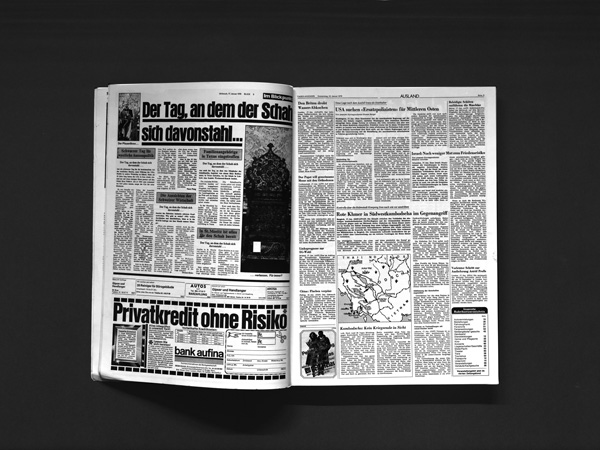

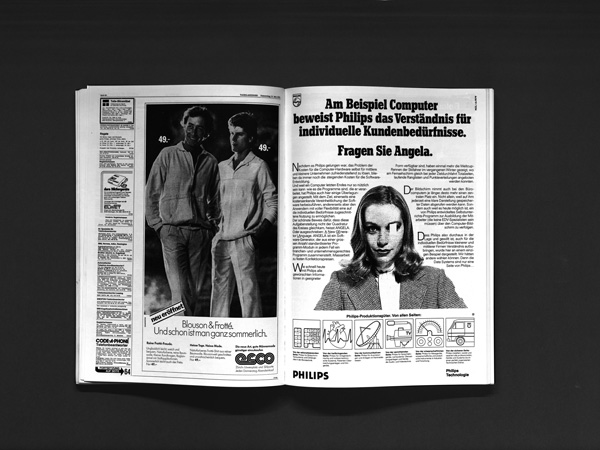

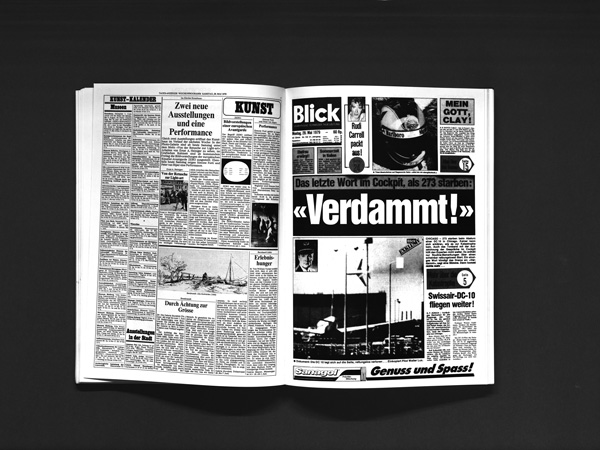

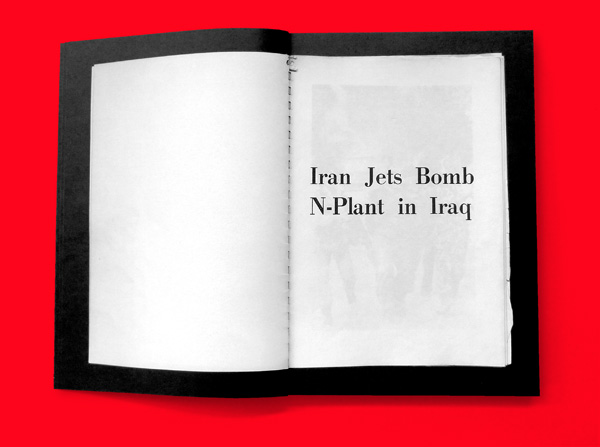

The idea behind 1979 is simple: for every workday of the year, one page of a daily Swiss newspaper has been reproduced, showing events of local and international political significance. That makes up the first volume, here on the left.

â1979, Eine Art Geschichteâ

2 volumes, 312 pages each

brochure, 20,8 x 29,4 cm

Verlag Hans-Rudolf Lutz, 1980

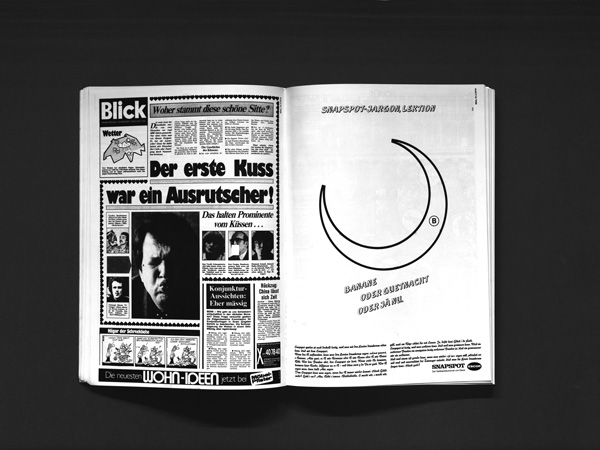

Volume 2: A 10 x 15 mm section has been cut out of each of these pages and enlarged to fill the book format of 208 x 294 mm, as you can see on the right hand side.

â1979, Eine Art Geschichteâ

2 volumes, 312 pages each

brochure, 20,8 x 29,4 cm

Verlag Hans-Rudolf Lutz, 1980

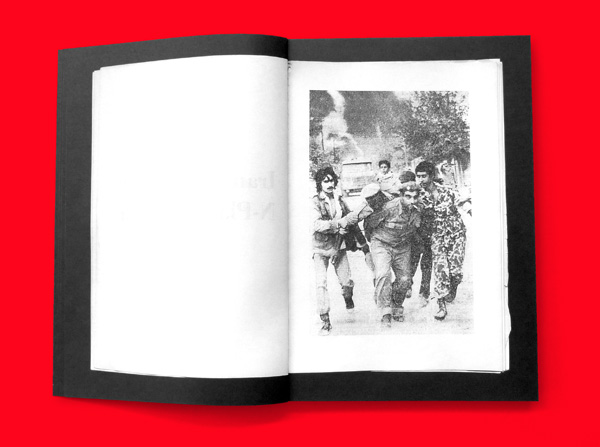

We will first of all show you spreads from Volume 1:

â1979, Eine Art Geschichteâ

2 volumes, 312 pages each

brochure, 20,8 x 29,4 cm

Verlag Hans-Rudolf Lutz, 1980

â1979, Eine Art Geschichteâ

2 volumes, 312 pages each

brochure, 20,8 x 29,4 cm

Verlag Hans-Rudolf Lutz, 1980

â1979, Eine Art Geschichteâ

2 volumes, 312 pages each

brochure, 20,8 x 29,4 cm

Verlag Hans-Rudolf Lutz, 1980

â1979, Eine Art Geschichteâ

2 volumes, 312 pages each

brochure, 20,8 x 29,4 cm

Verlag Hans-Rudolf Lutz, 1980

â1979, Eine Art Geschichteâ

2 volumes, 312 pages each

brochure, 20,8 x 29,4 cm

Verlag Hans-Rudolf Lutz, 1980

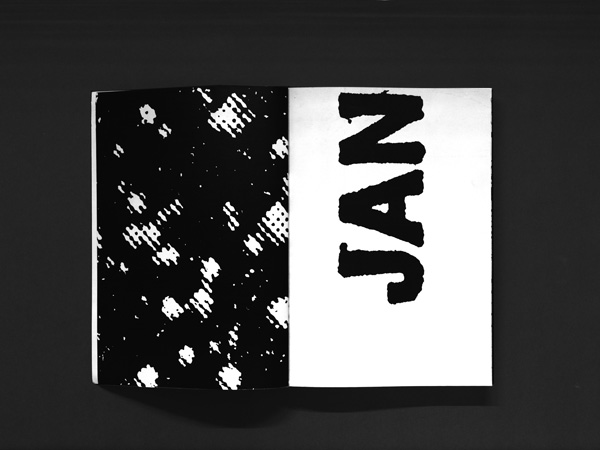

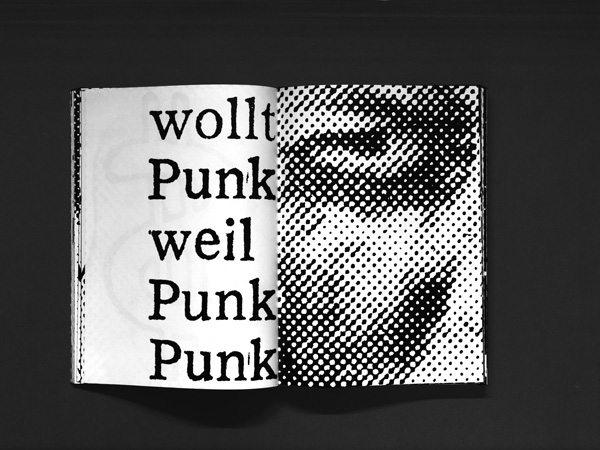

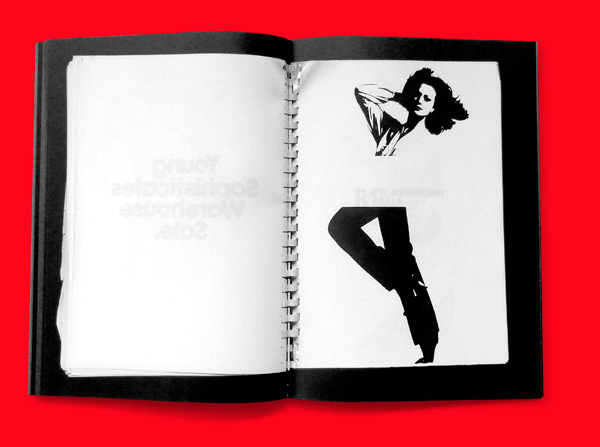

Volume 2: The clippings have not been selected at random. They are meant to offer a visual commentary on the largely verbal news in the first volume. The outcome is volume two and also a history of the year 1979: âa story in signs and pictures.â

By isolating and enlarging, what is missing in Volume 1 takes on a substantially different appearance and other formal characteristics.

â1979, Eine Art Geschichteâ

2 volumes, 312 pages each

brochure, 20,8 x 29,4 cm

Verlag Hans-Rudolf Lutz, 1980

It tends to be more vivid

â1979, Eine Art Geschichteâ

2 volumes, 312 pages each

brochure, 20,8 x 29,4 cm

Verlag Hans-Rudolf Lutz, 1980

provokes associations,

â1979, Eine Art Geschichteâ

2 volumes, 312 pages each

brochure, 20,8 x 29,4 cm

Verlag Hans-Rudolf Lutz, 1980

completes,

â1979, Eine Art Geschichteâ

2 volumes, 312 pages each

brochure, 20,8 x 29,4 cm

Verlag Hans-Rudolf Lutz, 1980

emphasizes

â1979, Eine Art Geschichteâ

2 volumes, 312 pages each

brochure, 20,8 x 29,4 cm

Verlag Hans-Rudolf Lutz, 1980

or changes, what in Volume 1 still seemed to be understood as a logical meaning.

â1979, Eine Art Geschichteâ

2 volumes, 312 pages each

brochure, 20,8 x 29,4 cm

Verlag Hans-Rudolf Lutz, 1980

âWhile we tend to have a better grasp of visual and textual relations in volume 1, volume 2 gives us more insight into structures and pictorial signs that signalize something, that appeal to or even assault the emotions.â Fritz Billeter

Peter Rautmann, Professor for theory and history of aesthetic practices and former dean of the Hochschule of Arts Bremen, wrote to Lutz in 1986:

âThis is in my mind a quality of your history book, that it constantly leads us to think about the basic aesthetic-philosophical problems of our existence.

How can a current event be qualified, how can we find our way around in the world of events, in this original chaos, how does the small, seemingly peripheral detail relate to the whole, what criteria can we accept for ourselves, how can we assert ourselves as subjects in this âoceanâ of happenings.â

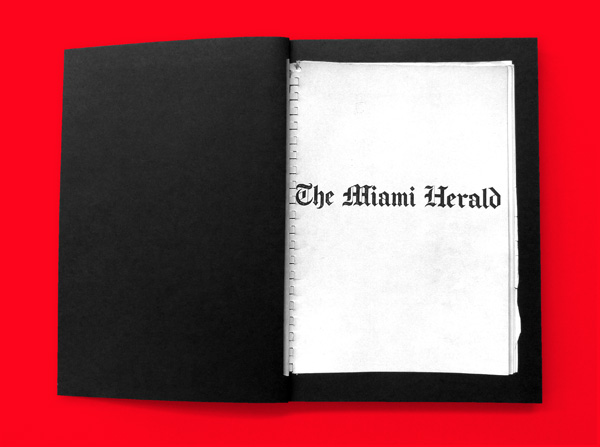

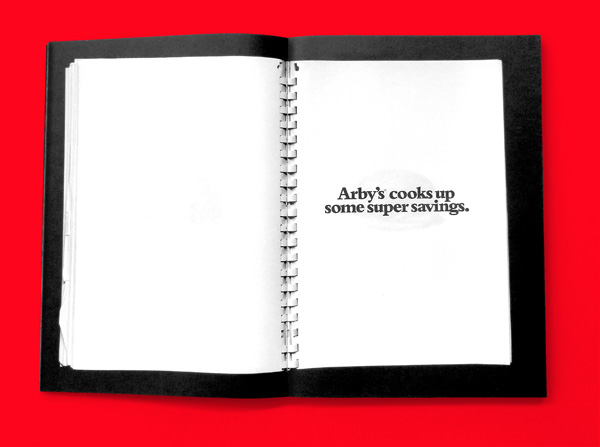

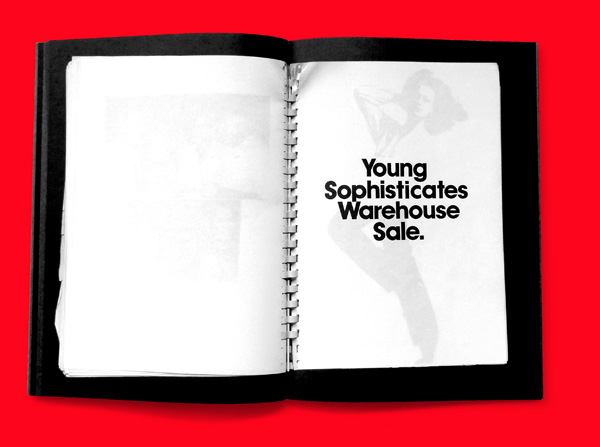

âThe Miami Herald, Wednesday, October 1, 1980â

âThe Miami Heraldâ

Hans-Rudolf Lutz

Wednesday, October 1, 1980

Reissue of originally 8 books published by Hans-Rudolf Lutz, Zurich, 1980

First edition of 80

© everyedition, Zurich, 2013

We will now present the project âThe Miami Heraldâ by Hans-Rudolf Lutz.

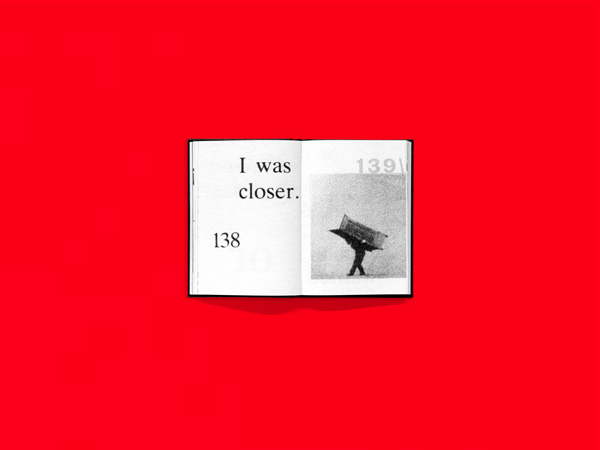

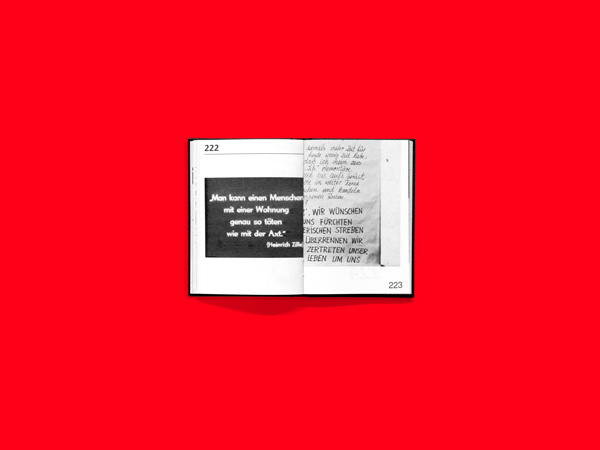

The model Hans-Rudolf Lutz used for this project was the 1 October 1980 issue of âThe Miami Heraldâ, out of which he cut a text with a contentually associated picture and then assembled them behind each other. The order of the printed pairs of text and picture corresponds to their order in the newspaper.

We reissued âThe Miami Heraldâ this year, which has just been published by everyedition.

âThe Miami Heraldâ

Hans-Rudolf Lutz

Wednesday, October 1, 1980

Reissue of originally 8 books published by Hans-Rudolf Lutz, Zurich, 1980

First edition of 80

© everyedition, Zurich, 2013

This new edition shows the only to our knowledge existing and quite battered original as a book in the book.

âThe Miami Heraldâ

Hans-Rudolf Lutz

Wednesday, October 1, 1980

Reissue of originally 8 books published by Hans-Rudolf Lutz, Zurich, 1980

First edition of 80

© everyedition, Zurich, 2013

Lutzâs first edition consisted of 8 copies, we have limited the new edition to 80 copies.

âThe Miami Heraldâ

Hans-Rudolf Lutz

Wednesday, October 1, 1980

Reissue of originally 8 books published by Hans-Rudolf Lutz, Zurich, 1980

First edition of 80

© everyedition, Zurich, 2013

The âMiami Heraldâ represents to us one of his most radical projects.

âThe Miami Heraldâ

Hans-Rudolf Lutz

Wednesday, October 1, 1980

Reissue of originally 8 books published by Hans-Rudolf Lutz, Zurich, 1980

First edition of 80

© everyedition, Zurich, 2013

Lutz brings the concept to the point with this short and concise statement: âUsing a verbal message to announce a visual one.â

âThe Miami Heraldâ

Hans-Rudolf Lutz

Wednesday, October 1, 1980

Reissue of originally 8 books published by Hans-Rudolf Lutz, Zurich, 1980

First edition of 80

© everyedition, Zurich, 2013

âThe Miami Heraldâ

Hans-Rudolf Lutz

Wednesday, October 1, 1980

Reissue of originally 8 books published by Hans-Rudolf Lutz, Zurich, 1980

First edition of 80

© everyedition, Zurich, 2013

âThe Miami Heraldâ

Hans-Rudolf Lutz

Wednesday, October 1, 1980

Reissue of originally 8 books published by Hans-Rudolf Lutz, Zurich, 1980

First edition of 80

© everyedition, Zurich, 2013

âThe Miami Heraldâ

Hans-Rudolf Lutz

Wednesday, October 1, 1980

Reissue of originally 8 books published by Hans-Rudolf Lutz, Zurich, 1980

First edition of 80

© everyedition, Zurich, 2013

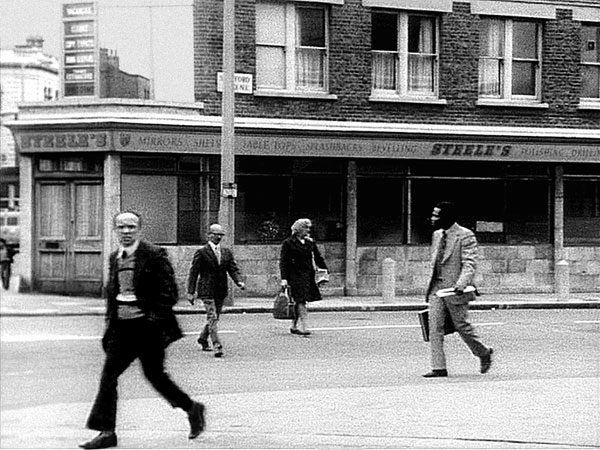

âThe Girl Chewing Gumâ, John Smith

By the following correlation, the film âThe Girl Chewing Gumâ, which was created at about the same period as âThe Miami Heraldâ, the artist John Smith also addresses the temporal relation between verbal and visual messages.

Unfortunately, we cannot show you this 12-minute avant âgarde film in its full length.

In âThe Girl Chewing Gumâ, a commanding voice seems to be directing the happenings of a busy London street. As the film goes along, the orders become more and more absurd and we realize, that the alleged film director is merely a fictitious film director. The scenes do not comply with the voice, but the opposite.

âSmith embraced the âspectre of narrativeâ […] to play word against picture and chance against order.â

A. L. Rees, 1995

âThe Girl Chewing Gumâ

John Smith

(1976) 12 mins, B/W, Sound, 16 mm

âThe Girl Chewing Gumâ

John Smith

(1976) 12 mins, B/W, Sound, 16 mm

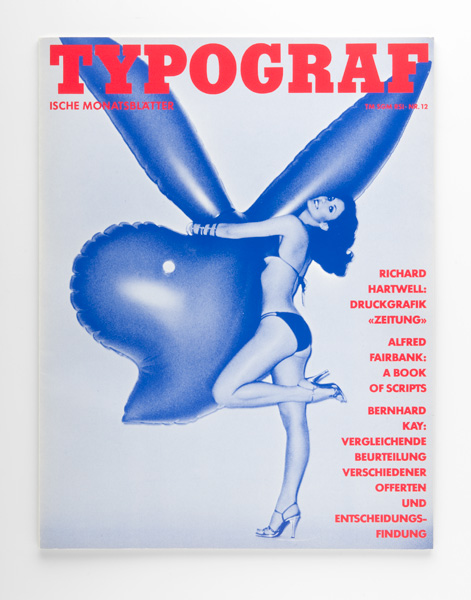

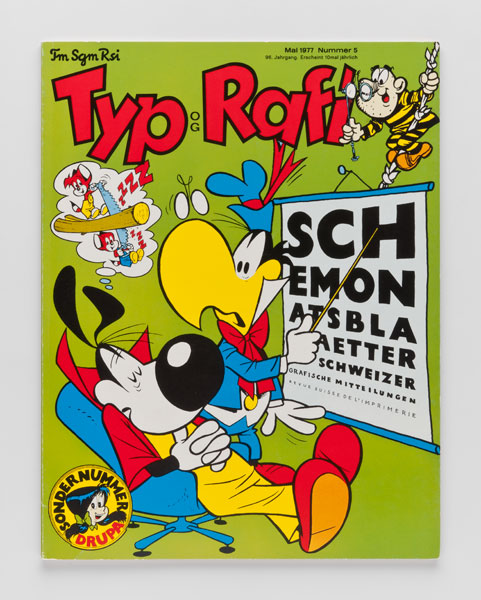

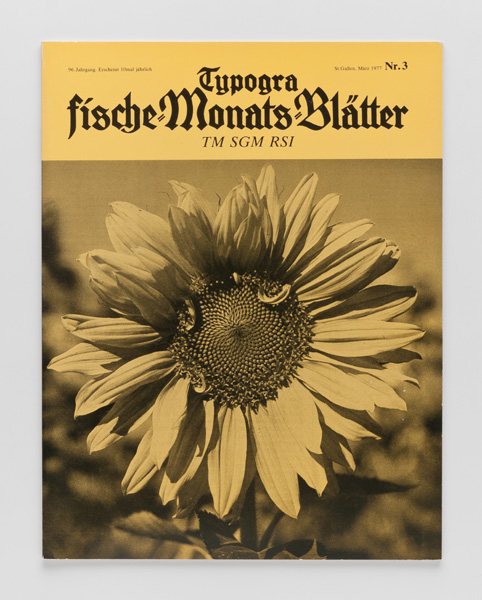

âTMâ

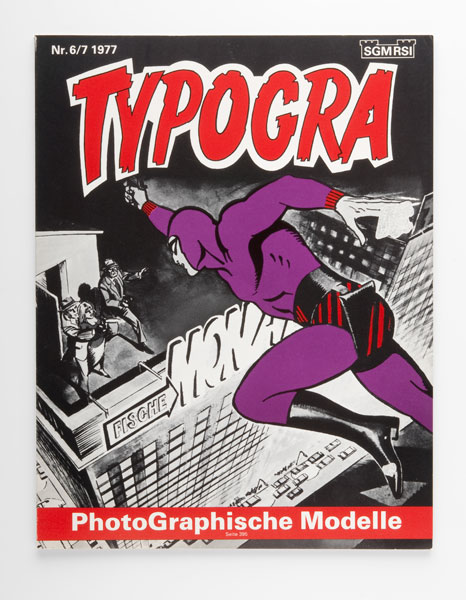

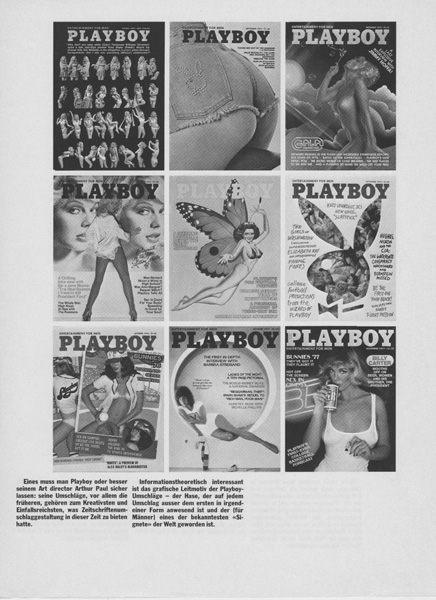

Another very well known work by Hans-Rudolf Lutz concerning the relation between word and picture are the covers for the Swiss magazine âDie typografischen MonatsblĂ€tterâ.

TM

By the covers for the TMâMagazine, Lutz wanted to show that the visual message of plagiarized design concepts momentarily usurps the verbal message of the text.

TM

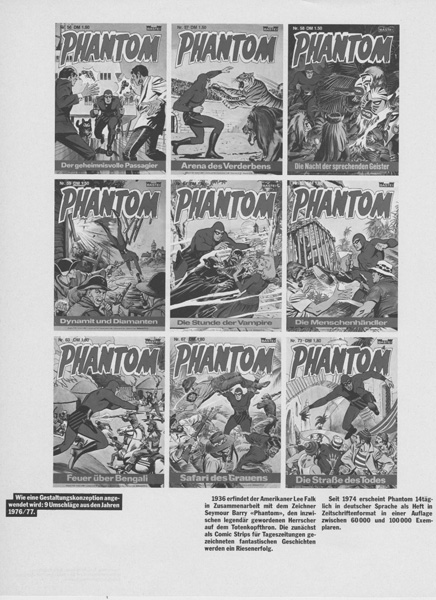

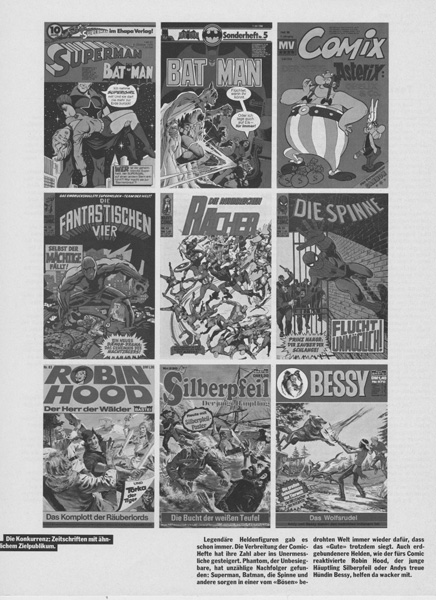

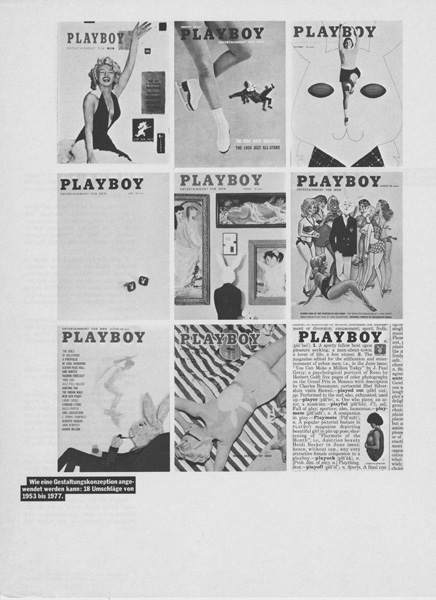

In 1977, 12 plagiarizations are published of Schweizer Illustrierte, the Tages-Anzeiger-Magazin, Gelbes Heft, Pop, Fix und Foxi, Beobachter, Phantom, Neue Post, Elle, Der Spiegel, Time and Playboy.

TM

Looking back at his apprenticeship as a typesetter, Lutz writes: âthe Typografischen MonatsblĂ€tter have a good reputation and regularly provide food for controversy. Especially the special issues on âSwiss designâ are very controversial among the typesetters. The bosses are quite generous when it comes to participation in TM-competitions and authorize the use of the setting equipment beyond working hours.â

TM

Albert Kapr, typographer and calligrapher, author and up until the 80âs professor for writing and book design here at the Hochschule for design and book art comments:

âThe rule seems to be that you can ignore the figurative aspect of writing when you are reading, that only the ideas that we read sink in; yet the shape of the letters and their typographic arrangement operate unconsciously upon the reception of the ideas that are loaded onto the visual shapes, they can weaken or strengthen their effect.â

TM

TM

At the beginning of the work on the TM covers Lutz writes to numerous magazine publishers asking them to support him in this project. He requested past issues, in order to examine the application of the design concept.

With computers, word and image are produced by the same machine for the first time. The crossovers between the media have thus become much more fluent.

âThat could also mean: ranking the âverbal legibilityâ after the âvisual legibilityâ and as such building upon the expressiveness of the form and not the content of the signs.â

Hans-Rudolf Lutz, 1991

TM

This information, as well as figures and facts about the number of copies, diffusion, etc. and also the comparison to competing products are shown by him on a spread in each respective TM-Magazine.

TM

For this TM-Cover concept, Lutz had to ask several publishing houses for permission to plagiarize their design concept. This was most certainly a difficult undertaking knowing that all the major and successful publishers dispose of legal departments, who are schooled to ward off plagiarizing attempts.

The publishing director of the Spiegel, for instance, started off by refusing the permission with the reasoning that it is legally not defendable to authorize some to plagiarize and forbid it to others.

TM

âEspion, lĂšve-toiâ, 1982

âEspion, lĂšve-toiâ, 1982

Director: Yves Boisset

âEspion, lĂšve-toiâ, 1982

Director: Yves Boisset

âEspion, lĂšve-toiâ, 1982

Director: Yves Boisset

âEspion, lĂšve-toiâ, 1982

Director: Yves Boisset

âEspion, lĂšve-toiâ, 1982

Director: Yves Boisset

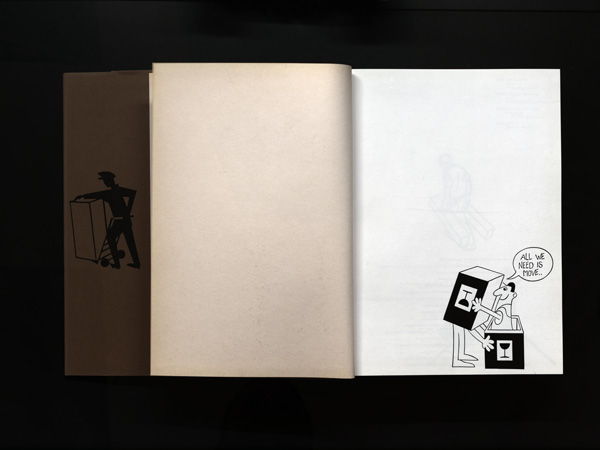

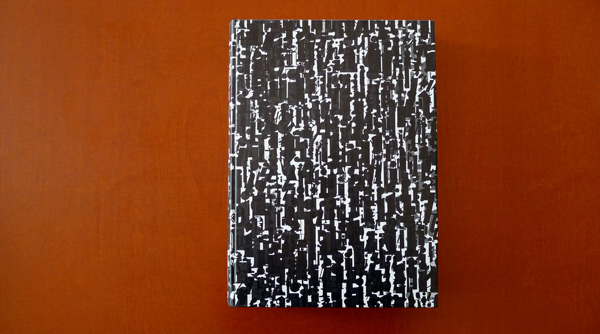

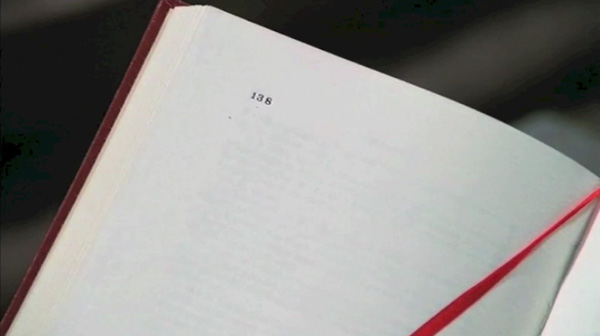

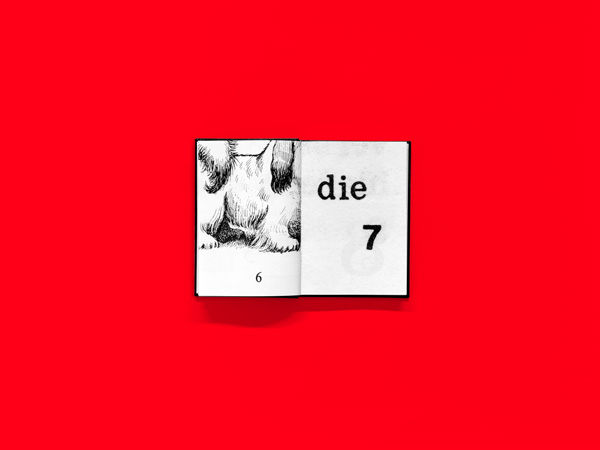

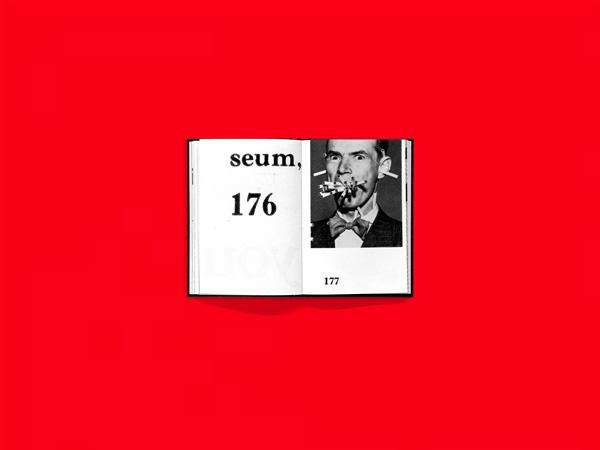

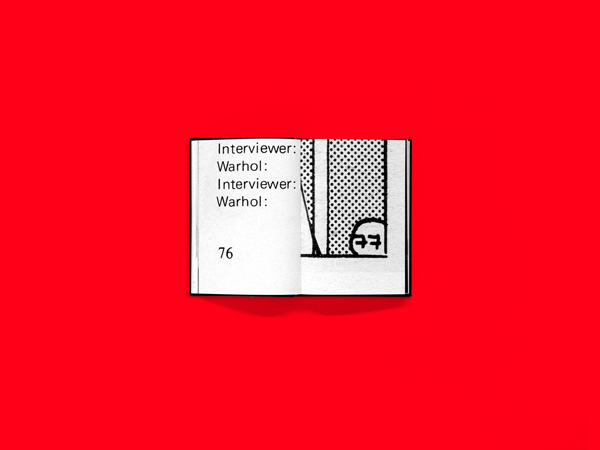

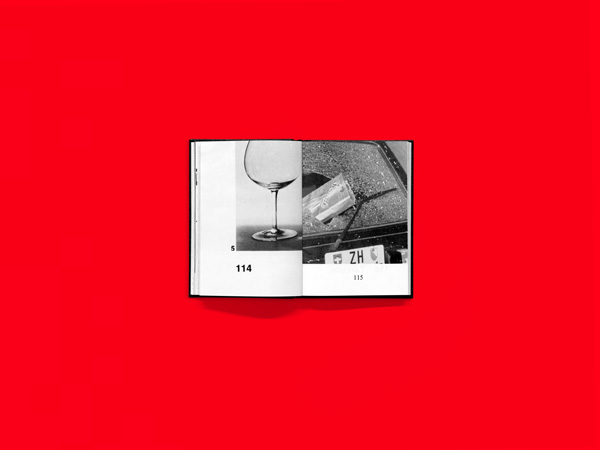

â336 pages 336 booksâ, Tania Prill, Alberto Vieceli, Sebastian Cremers, everyedition, 2013

â336 pages 336 booksâ

Tania Prill, Alberto Vieceli, Sebastian Cremers,

everyedition, 2013

The last project that we are presenting today is not by Hans-Rudolf Lutz, but a book by Alberto, Tania and myself, that has just been edited by everyedition.

â336 pages 336 booksâ

Tania Prill, Alberto Vieceli, Sebastian Cremers,

everyedition, 2013

Tania, Alberto and I work together for our commissioned work as well as for our self-initiated projects.

For this 336-page book we have sighted thousands of books of all different periods, on different topics and focuses, in search of 336Â headstrong, incorruptible and humoristic page numbers.

â336 pages 336 booksâ

Tania Prill, Alberto Vieceli, Sebastian Cremers,

everyedition, 2013

â336 pages 336 booksâ

Tania Prill, Alberto Vieceli, Sebastian Cremers,

everyedition, 2013

On one spread, 2 pagings face each other, they relate to each other by their setting. The entirety of the pages reflects the visual diversity of the world of books.

â336 pages 336 booksâ

Tania Prill, Alberto Vieceli, Sebastian Cremers,

everyedition, 2013

The inspiration for this project comes from all sorts of directions.

â336 pages 336 booksâ

Tania Prill, Alberto Vieceli, Sebastian Cremers,

everyedition, 2013

The dramatic composition and the structure of our book refer to the wonderful book by George Brecht: âbookâ, which addresses the phenotype of books in a self-referring approach.

â336 pages 336 booksâ

Tania Prill, Alberto Vieceli, Sebastian Cremers,

everyedition, 2013

The title is inspired by the artist books by Ed Ruscha. His book titles often describe the content.

â336 pages 336 booksâ

Tania Prill, Alberto Vieceli, Sebastian Cremers,

everyedition, 2013

The underlying idea to â336 pages 336 booksâ originated when reading page 243 of Bram Stokerâs âDraculaâ, (1967).

â336 pages 336 booksâ

Tania Prill, Alberto Vieceli, Sebastian Cremers,

everyedition, 2013

A leaflet with the index of the source references is enclosed in the book.

â336 pages 336 booksâ

Tania Prill, Alberto Vieceli, Sebastian Cremers,

everyedition, 2013

With this project, the reissue of âThe Miami Heraldâ and this lecture, we would like to open and revive the Hans-Rudolf Lutz archive. Even if we work under different circumstances with our own studio, our teaching and publishing activities, Hans-Rudolf Lutz influences our practice by his work and his posture.

Thank you.

everyedition.ch verlag-lutz.ch Copyright for the images © Tania Prill, Verlag Hans-Rudolf Lutz