Répondre à Johnc957 Annuler la réponse.

by Florent Dubois, Julie Gufler and Julia Metropolit

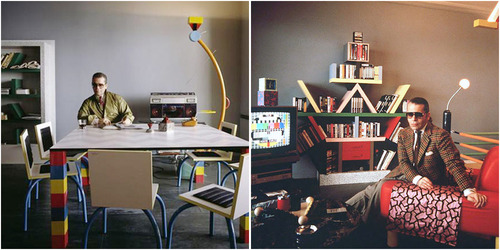

The Memphis collective in Tawaraya-Boxing ring (1981). On the right Ettore Sottsass

My sudden interest in Memphis was an infatuation. I had no idea about the history of design and wanted in fact to write a Master’s thesis on Disco and its progressive transformation from underground to mainstream.

I was seduced (perhaps too easily) by Memphis—as I imagine that the public was seduced at their very first presentation—by the quirkiness of it all. By the explosion of bright colors, the unusual assemblages of forms and materials; incongruous mixing of plastic laminate, glass, marble, granite, metal and lacquered wood. In short, by furniture as expressive as cartoon characters, or Hollywood divas: totem cupboards and vases erected like imaginary monuments, crooked chair feet, two- or three-legged ball- or cylinder-shaped tables; with tropical names. I was seduced by this self-sufficient and tarted up furniture, which was making a scene of itself and reminded me of disco dancers dressed to go chat up, or the New York nightlife personalities of a bygone era. Disco music seemed to me the perfect soundtrack for a presentation of Memphis furniture and vice versa; the pieces would have been the ultimate décor for the notorious first disco clubs.

Twiggy in the London fashion store Biba (1964)

Thus, before I knew the score, I found myself suddenly involved in a mess of correspondences and analogies between two subjects, which admittedly had no close connection except their deep ambiguity. The infatuation of course took precedence over the long-term interest in the end, and this is where this essay begins.

The Memphis group was founded during a long winter night, on December 11th 1980, in the living room of Ettore Sottsass. Around a glass of white wine and with a Bob Dylan record playing in the background, Sottsass—famous architect and designer at that time in his 60s—was discussing the world with young designers working at his agency: Marco Zanini, Aldo Cibic, Matteo Thun, Michele de Lucchi, and Martine Bedin. George Sowden and Nathalie du Pasquier were yet to join. Sottsass’ partner Barbara Radice, journalist and future art director of the group, was also present.

That evening, The Memphis Group was not yet mentioned, but everyone agreed that suede beige sofas, chromed steel tables with tinted glass plates, walls with modular bookcases, carpets in all the shades of earth—in short, all the “good” design array of the 70s—would not have a place in their project (Radice 1984).

As the night went on, nobody was thinking of changing the tune of Dylan, repeatedly singing Stuck inside of mobile/With the Memphis blues again, and suddenly the name Memphis got everyone’s attention; as the prophetical evocation of strange and mythical worlds meeting: in Radice’s words “Blues, Tennessee, rock’n’roll, American suburbs, and then Egypt, the Pharaohs’ capital, the holy city of the god Ptah (patron of the craftsmen, eds.)[…]” (Radice 1981). February 1981, more than a hundred colorful drawings proved that the new design of Memphis, more than an exaltation of a group of tipsy friends, had become a reality. Their sketches of crazy décors with asymmetrical shapes revealed an addition of a bit of soul to inanimate objects until then devoid of it. At the Milan Furniture Fair in September 1981, people came in droves to see the fifty-five first pieces of The Memphis Group. Memphis was on everyone’s lip, the show was a striking success and the design group quickly became a cult movement.

Twiggy in Biba by Justin de Villeneuve (1964)

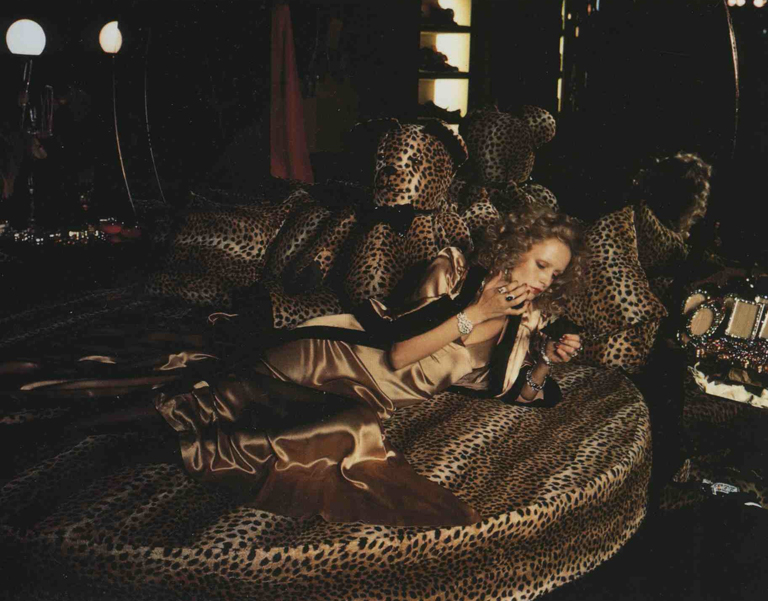

A glamourous and over-done universe was what first caught my interest in Memphis, but I was quickly disappointed by discovering the scarcity of any presentation photos whatsoever of Memphis furniture pieces together—mise-en-scène—with living people, their inhabitants or users. One photo, of the Vanity (1982) chest of drawers, taken by Memphis collaborator Hans Hollein seems to me to hint at the performative and lascivious relation, which I was longing to find; this gentle coming out of oneself, a Camp transformation resulting from an interaction with the objects. Official photos of the Biba boutique in London play in the same register. But unfortunately, it appears that we are still not in the presence of Memphis furniture.

Hans Hollein, Vanity (1982)

It is striking how Memphis seems to have become, and remains, cult and collector’s item, not in retrospective—as it is usually the case if that happens with furniture and other cultural products—but before it ever was anything else (such as a piece of furniture, serving living space purposes of one or more inhabitants). In this sense, there is, paradoxically, something uninhabitable, or unapproachable to Memphis furniture. An unapproachability, which is echoed in the infatuation and desire—the secret balance between shock, offense and fascination—which the pieces invoke in us, when we see and experience them, and which makes it so difficult to rationalize in words what they are all about.

At least for the time it will take you to read this essay, I will instead attempt to get closer by analyzing and discussing how two socio-cultural phenomena, which I argue are at its core, unfold and intersect in the design of The Memphis Group. The two related phenomena are on one hand Occasions, with which I have chosen to denote the interactions, which occur when a piece of furniture is confronted with its user(s); on the other hand Transformation, which I argue unfolds on multiple levels during these interactions and constitute an integral part thereof.

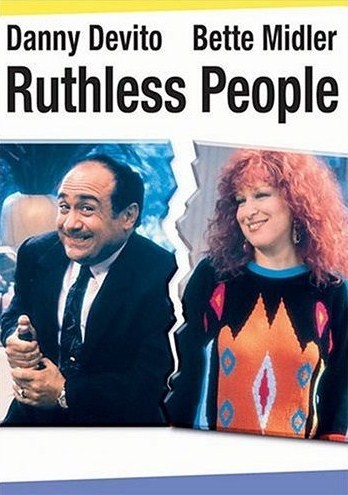

My essay will start out with a characterization of Memphis’ design, pointing out the influence of Minimalism and Functionalism, which make up important conceptual and historical components in the context of which Memphis’ designs were developed. In the second and third chapters, I will then first analyze and discuss the Occasions, which I argue that Memphis furniture implies in particular; secondly, I will analyze the 80s cult movie Ruthless People (1986) with respect to the Transformation, which constitutes an integral part of these occasions, and thus can be said to be characteristic of Memphis furniture,. Finally, I will conclude upon how the two phenomena intersect in the work of The Memphis Group, and what this means in a wider socio-cultural perspective.

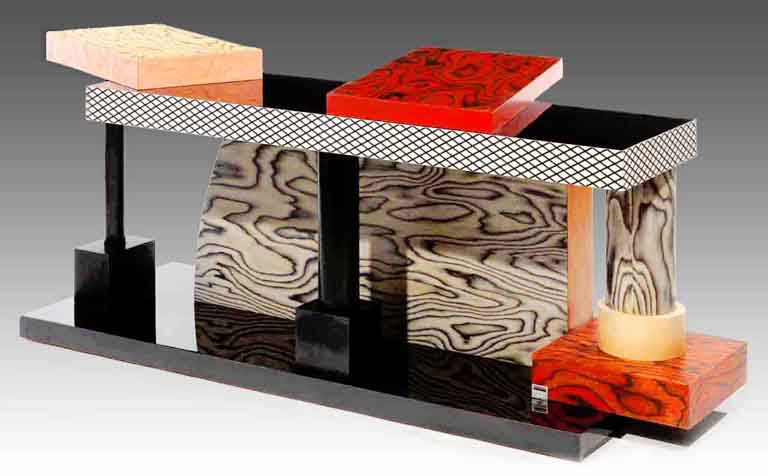

Beverly (1981)

Liminal Furniture

•••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••

Memphis furniture called into question the dominating taste of its time, marked by formal unity and homogeneity. Influenced by traditional Japanese design and architecture, so-called minimalist design of the 60s and 70s had at its core the conception and manufacturing of a smooth and homogeneous structure to which the surface constituted an integral part.

The Memphis Group’s apparently unstructured chest of drawers, Beverly (1981), hints at this discussion with Minimalism, while indicating that the design of the Memphis group is, on the contrary, not conceived as a unit or a whole, but rather as a sum of parts. The piece has a speckled-green laminated wood sideboard at its base, on which a tube of chromed steel with a red bulb seems to hold together a slanted part of a interimistic Briar root wooden shelf. The bulb’s electrical cord is hidden inside the tube and continued into the sideboard base, finding its output on the latter’s lover right. Finally, additional small stumps of matching signal-colored laminated wood shelves stick out orthogonally and just above the ensemble’s middle on either side.

The material of the chromed steel tube and its function as hiding the electrical cord carry quite evident references to minimalism, while its simultaneous function as lamp post for a seemingly decorative red bulb does not entirely fit into such a principle. The internal contradiction or ambiguity inherent in the piece with regard to its parts is emphasized structurally as well as on the surface, and this is true when we regard the ensemble as a whole as well: Structurally, the sideboard is diverted from its vertical axis by the added elements and seems on one hand to be pushed away from the tube, on the other to be held together by it, and vice versa. The visual collage of different material surfaces and colors, which we recognize from art, is probably what on first sight appears the main “reason” for the impression of un-structure, but paradoxically, it is one of the piece’s most simple combinations: laminated wood, wood and steel; signal red and green combined with non-colored/”natural” colors.

Finally, Beverly is representative of the cultural collage, which is a trademark of The Memphis Group. References are in a somewhat profane manner mixed and matched, from the African symbols of the geometry and the speckled green laminate, to the signal colors of a children’s room or of streetlights, to the self-made wooden shelf of the “primitive” and less privileged worker or peasant, which could also just be a shelf in the urban nuclear family’s basement workshop, where dad reigns in a “doesn’t care” manner, or even the rustic shelf of the modern new-bourgeois rural country house. Is the red bulb that of a go-go bar, or just a practical way of warning us at a film set?—we could continue this game in circles for hours without setting at any clear answer.

But if anything, we can conclude that a negotiation of limits indeed seems to be at play in the furniture of the Memphis group. This dynamic does not simply imply that we look at existing power structures in a new way and change our outlook accordingly; Memphis furniture requires that we as users consciously position ourselves in the border land, on the margin, where notions and discourses are negotiated, so that it is the transgression as a movement, which is put at the center.

Carlton (1981)

The liminality of Memphis’ furniture consists as much in the furniture itself as in the users’ self-critical being. The perhaps most famous piece of Memphis furniture, Carlton (1981), is a large free-standing wood and plastic laminate multi-colored object, which shares some characteristics with furniture that we usually attribute the functions of a shelf system, or a room divider. Again, the multi-functionality of this piece is a characteristic, which could be said to be shared with Minimalism (Cf. the German-American architect Mies van der Rohe’s statement Less is more), but its anthropomorphic structure and the many diagonal lines quickly obscure this.

Because Carlton is above all totemic-looking, the action of attributing function—rather than the actual attribution, which ensues—seems indeed to be at the center of this piece; a totem being the ultimate emblem of the fetichized object. Provided that we accept Carlton as a piece of furniture, its mere existence implies immediate questions of what and how; what kind of furniture is this, and how do we use it? Say for instance that we understand Carlton as a room divider, then there is a fundamental lack in its function, ascribed to the fact that it consists largely of holes; indeed, it seems to be more revealing and merging than it is covering up or dividing space. Similarly, if instead we understand Carlton as a shelf system—for books for instance—there is a fundamental lack in its function ascribed to the fact that it is not systematic; because its slanted dividers do not support an upright position but prevents it, and because the majority of “ineffective” space due to asymmetry separates, rather than it assembles.

Just like in that of the animal, there is a mimicry in Memphis’ furniture, which is at once a copy, a mocking and an homage. This mimicry plays on, and thus accentuates, the shift between what we as human beings and users recognize and can identify with, and something other and more – a kind of distortion or expansion. As users, we are prevented from categorizing Carlton according to the normative categories that we know for furniture; we will either have to invent new categories, or we will have to incorporate the lacks and additional functions of this particular piece into the existing notion that we have, expanding and thus transforming our norms for what room dividers and shelf systems are, and how they are, i.e. which function(s) they embody.

Memphis pieces in this way claim a discussion of what and how in furniture—that is to say, a discussion between form and function. This question calls to mind the slogan form follows function, coined in the 1880s by one of the pioneers of modern architectural design, the American architect Louis Sullivan. With the phrase, Sullivan implied that a building should be determined by practical considerations such as use, material and structure, as distinct from the attitude that plan and structure must conform to a preconceived picture in the designer’s mind. Functionalism—the principle to which Sullivan’s phrase is today widely ascribed as one of the major representatives—was thus at its outset an architectural one, but from the beginning of the 20th century and onwards, it began to be discussed and applied more broadly as an aesthetic approach. One of the most influential aesthetic approaches in 20th century Western architecture and design, Functionalism is another evident example of the contemporary context to which Memphis’ furniture can be seen as a reaction.

Tartar (1985)

Furniture as an occasion

***************************************

Another of Functionalism’s catchphrases is the Swiss-born architect Le Corbusier’s dictum, a house is a machine for living in (1920). With this phrase, Le Corbusier meant to hint at and encourage the importance and positive force of the technological revolution on people’s lives. In addition to an immediate enthusiasm for technology however, one could also read Le Corbusier’s phrase as representative of Functionalism’s general vision of an architecture and a design based on rational and scientific thinking, which is foremost at the service of the modern user: architecture and design as a tool for solution. According to Sottsass, Memphis furniture was clearly a reaction, and an attempt to create an alternative, to this vision:

We were refusing to think design as a solution to anything—which is an essential postulate of the modern movement for which creating a chair, or a table would mean to try to solve the problem of the chair or the table. We were estimating that it was not the case, because for us there was no such thing as a problem to solve.

(Sottsass 1994)

If a piece of furniture is not functional in the sense of being meant to solve a problem of the user in the house, one might ask for what then, it is meant? In the above, I have delimited the most important aspects as to how Memphis furniture poses questions to its users, how it provokes a continuously self-critical approach because the user must make decisions and judgements about it, only to have to change them again, on and on.

In my opinion, it is misunderstood to directly “read” the polemics of Memphis’ furniture as an allegoric message about human relationships, e.g. attributes—dress, things owned, job, etc.—are not indicators of an essential “character” and the person should be seen separate from his or her attributes; this would be the kind of problem-solving and normative didactics, which Memphis according to Sottsass is reacting against. Rather, in separating the object and the directions for its use, in pointing to the possible distinction between a form and its function, Memphis furniture becomes an occasion for one or more users to interact in and thus discuss these issues, not so much in terms of rhetorics, but with their bodies. Carlton, which imitating a totem does not—as for instance traditional shelf systems of its time—has a front- and backside, in a very literal way invites to such interactions or meetings, from one room (of one’s own) to another.

Another important element of this bodily exchange manifest in Carlton is color: Red, blue, green, yellow, orange, black—signal-, warm, cold and pastel hues combined. Provoking strong reactions in the brain, color is a characteristic element in Memphis pieces calling upon the user’s consciousness. Thus, Barbara Radice explains how

Color works as an enzyme to catalyze chemical reactions” and “generates nervous impulses that open new doors of logic in the brain, it is a sort of perceptive jogging, an aerobic for lazy or drowsy sensory cells. Like jogging, it requires commitment, determination, measure, enthusiasm, faith, and patience; and to serve a purpose, it must be used well.

(Radice 1984)

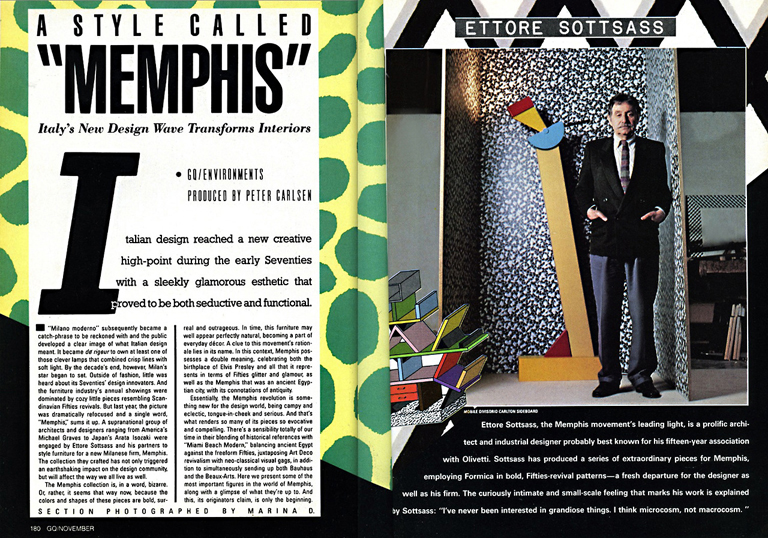

Nov. 1982 GQ Magazine article on Memphis-Milano design.

More than just catching the attention as a visual trick of making itself more commercializable, color in Memphis furniture is something, which relates to emotions and engages with the user through a language that surpasses its mere visual aspect, placing the user as a specific individual at the center of its process. As such, the seductive potential of the piece of furniture—and the user, which enacts with it—prevails over its functionality, affect and charm being its main component; as directly escaped from imagination, rather than built out of rational thinking. The expressive and emotional relations between user and furniture are brought up out of seduction, fantasy and narration. Rather than being grounded in a firm origin, the object seems to be chattering with references, and is placed at the center of the design process in order to be the place of new human relations.

The house becomes in this way a place of mental and poetical constructions, rather than an efficient answer to needs of comfort— a total and fantastic universe to be invented for its inhabitants.

Memphis as Transformation in Ruthless People

•••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••

In the above, I have discussed how Memphis plays on the contradictions between on one hand the plastic, social, and cultural materials of the furniture pieces, and on the other the environment in which they will be put into function.

Sam in the Stone’s bedroom

In the black comedy Ruthless People (1986), Danny DeVito plays an upstart clothes brand manufacturer, aka the spandex miniskirt king Sam Stone, that has not got so much of a professional and personal ethics. He lives in a large country house with his rich wife Barbara Stone (played by Bette Midler), whom he wants to kill in order to recover her large inheritance. Before he succeeds in this scheme however, a couple of Sam’s ex-employees kidnap Barbara to get revenge on Sam for having stolen their fashion design and fortune, thus unwillingly anticipating his wishes; of course, a haphazard chain of absurd attempts at blackmail and revenge—implying also Sam’s golddigger mistress—entails. A rare example of its kind, Ruthless People features Memphis furniture and a protagonist, Barbara, who without ambiguity and with a user’s enthusiasm has decorated the couple’s mansion entirely with Memphis replica.

Ruthless People (1986) cinema poster

The American writer and filmmaker Susan Sontag broke into mass celebrity upon the publication of her 1964 essay “Notes on Camp”. Sensationally structured somewhere between a dairy and a manifest, her list of 58 points described ”the sensibility—unmistakably modern, a variant of sophistication but hardly identical with it—that goes by the cult name of Camp. » Sontag points out that principally, Camp should be meant seriously: “[T]he essential element is seriousness, a seriousness that fails“. Like Sontag’s list, the ultimate definition of Camp is an accumulation of adjectives; it is exaggerated, overloaded, missing the point, baroque, failed, excessive, megalomaniac, pathetic, theatrical, naive and vulgar—but never intended (Sontag [1964]). The furniture of the couple’s mansion in Ruthless People is not the original Memphis pieces of a collector or a connoisseur, but heavily inspired to the point of some almost verbatim copies, as such featuring Barbara as the movie’s one and only absolute monarch, being the only one who is, ironically, “authentically” Camp.

Describing his wife’s tastes to his mistress, Sam remarks above all how he hate[s] the way she licks stamps, hate[s] her furniture. With the extravagant look of Barbara and her poodle, the furniture seems literally to be the straw that breaks the camel’s back in triggering Sam’s murderous drives.

As the farce unfolds, the audience witnesses a gallery of mistaken and mixed-up identities, where everyone seems to be unwillingly pretending to be somebody else. This is sometimes quite manifest, e.g. in the Halloween masks of the wimpy kidnappers and the happy face mimicry theater of Sam, whenever the police looks the other way (he is of course supposed to look sad). More subtly, we also discover how Sam’s mistress is not at all the loving partner in crime that she poses to him as, and how the county police officer is really just a dirty old man who is willing to compromise the law at the blink of an eye in order to keep this secret safe.

Ruthless People highlights in a comical way the unapproachability of the Memphis objects, which takes place when Barbara is gone. Sam, thinking of relaxing in an armchair looking like the Lido (1984) with Bacterio-patterned (1982) pillows has a lot of difficulties to sit down and ends up finding himself in a particularly uncomfortable position, when the phone rings for the first time. The pieces of furniture and the characters’ fruitless attempts to use them seems to me constitutive of their traits, as if they were not Camp » and sensitive enough to totally adhere to the Memphis furniture. Sottsass himself made jokes about the owners of Memphis furniture, saying that the pieces are “very intense” and could only co-exist with “very intense people, very highly evolved and self-sufficient people” (Sottsass quoted in Radice 1981).

Lido (1984)

Sam Stone in the living room as the phone rings

Barbara, on the contrary, has regular fist fights with the sparse furniture at her disposal in the middle-class cubicle house cellar imprisonment, which obviously does not meet her standards. In the course of the movie however, she gradually adapts to and appropriates it, so that it ends up feeling so homely that she wins over her kidnappers’ sympathy and trust. Visually being the only really dressed-up figure in the movie and furthermore spending her time of imprisonment in the cellar transforming the room into an improvised fitness studio and herself into the slim aerobic-diva version she had always wanted to, Barbara is also the only one who stays true to her character; this, seemingly because she does not need to pretend that she is continuously in transformation.

Similarly, as the movie unfolds along with Barbara’s transformation, all other houses and interior featured, such as the 50s pastels of the kidnappers’ cubicle house and the oddly African sci-fi antenna sculptures in the mistress’ boyfriends’ trailer caravan, seem to chat exceedingly of references to Barbara’s Camp Memphis-imitation mansion. At the films’ (anti-)climax when the embroilment finally vanishes into a disappearing act and the police case is justifiably solved, the transformed Barbara has realized her husbands’ cruel intentions, but reacts progressively by pushing him into the sea—the latter being namely a pompously symbolic act of guiding human beings into a new and transformed life.

Sam in the Stone’s dining room

The last scene visions Barbara on the beach, throwing herself into the arms of the couple, who has finally been freed of the forced pretension of being bad kidnappers, and whose fortune she as if by a magic trick has won back. All three walk off arm in arm towards the sunset and a new invented and inventive future, determined—on Barbara’s initiative and support—to start a fashion company together. The audience knows that Barbara will not go back to her Memphis-decorated mansion. Like the notorious German fashion designer Karl Lagerfeld—after having decorated his entire Monaco flat with Memphis furniture and used it for a single photo shoot—she does not need it any more; she has had her occasions and is moving on, going out into the world to seek other occasions and transformations, inventing for herself new life and places for her body to feel at home in the unknown.

Barbara Stone’s improvised fitness room in the kidnappers’ basement

Conceived to bring personality and individualism in design, The Memphis Group came quickly to an end, like all fashions. A striking commercial success, Sottsass left the group in 1984, after which it was finally dismantled in 1988. Laying out modes of life and of living, Memphis furniture granted new places for discussions, occasions for transformation. The immediate pleasure of creating without constraints, the lightness, the ephemerality, the decor, the humor, and the blending of cultures made it possible to redefine the act of creation in design.

Designer furniture was conceived by The Memphis Group not as timeless objects, but rather as products fluctuating in the same manner as fashion, sensitive to sudden changes and functioning according to the same quick model; with an outrageous look that appears to be for the season only. Contrary to the fashion of its time, however, Memphis embraced the ephemeral nature. Put in Sottsass’ words, “[w]e quote the present, and the future if possible. That is why we are very optimistic » (Sottsass quoted in Sottsass 1994, orig. in Designer n°2, 1982).

Karl Lagerfeld at his Memphis-decorated apartment in Monaco (1981)

In the above, we have seen how Memphis furniture is a topography in which the two related phenomena that I have denoted Occasions and Transformation play out and intersect. A user of Memphis furniture must continuously deal with the impossibility of categorizing the piece’s essence—what it is, and its function—how it is, according to normative standards. This is also true beyond a discussion of the history of design and architecture, as Memphis furniture constantly performs a mimicry: copying, mocking and paying homage to a vast reservoir of historical, social and cultural references. This means that while Memphis furniture via mimicry stays constantly in transformation, it also invites and inevitably draws the user into this transformation, and as such the pieces can be seen, rather than being mere objects, to constitute occasions.

This essay readily concedes that there is a Camp lure to Memphis furniture, but it also relates that this means that Memphis’ pretenses are meant dead seriously and thus without irony. Furthermore, this essay indicates that the mimicry inherent in Memphis thus conveys a meta-discussion about the ephemeral aspect so intrinsic to design, and to ideas as such; as the animal, which changes its surface into that of its surroundings when we try to come closer or even touch it, Memphis pieces transform themselves and can thus never really be used as such. Rather, by occasioning a transformation in the user herself, they push her away in an encouraging manner, invite her to look at what is next to herself, to go out into life and seek new occasions. To give Sottsass (Sottsass 1994) the last word: “It was like opening another window: Look there, there is another landscape, if you want, you can take a walk in it”.

This essay was first published in #2 of the publication series The Waves, edited by Julie Gufler and Julia Metropolit, as part of the exhibition series of the same name, which they curated at the Galerie der HFBK, Hochschule für Bildende Künste Hamburg, Apr – Jul 2014.

The online version of the publication series is accessible via issuu.com/the_waves and limited edition print versions coming up in fall 2014 will be published on the Materialverlag, Hochschule für Bildende Künste Hamburg (materialverlag.de). »

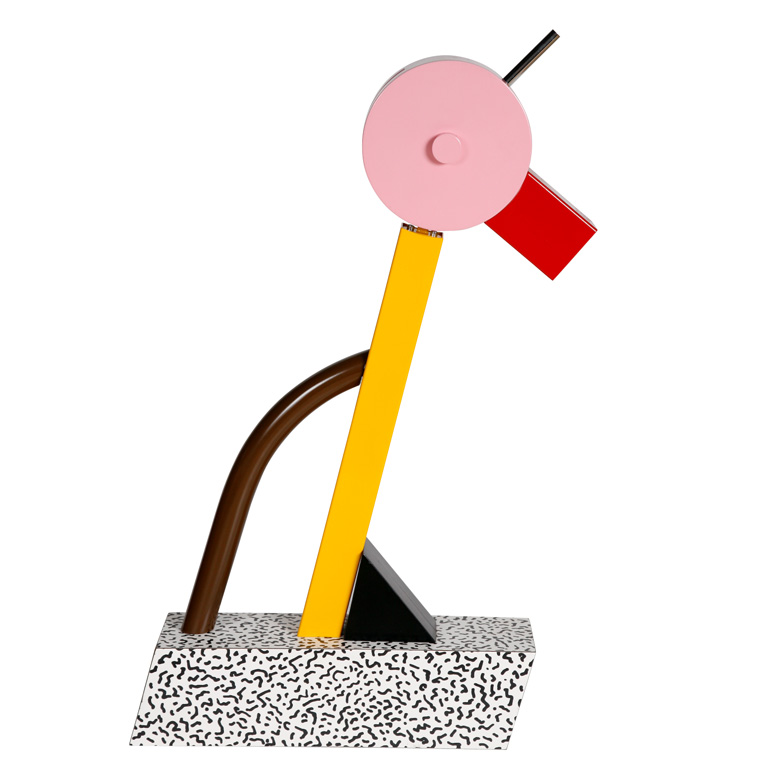

Tahiti Lamp by Ettore Sottsass (1981)

Sowden table clocks Acapulco, Excelsior, and American ‘81

Bibliography

•••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••

Radice, Barbara [1984]: Memphis: Research, Experiences, Results, Failures, and Successes of New Design, New York: Rizzoli, 1984

Radice, Barbara (ed.) [1981]: MEMPHIS, The New International Style, Milan: Mondadori Electa Spa, 1981

Sontag, Susan [1964]: “Notes on Camp” in Against Interpretation : And Other Essays, New York City: Picador, 1985

Sottsass, Ettore [1994]: Ettore Sottsass , Paris: Éditions du Centre Pompidou, 1994.

Filmography

****************************************

Ruthless People (Jim Abrahams – David Zucker – Jerry Zucker, 1986)

Furnitography

•••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••

Bacterio (Ettore Sottsass, 1982). Pattern for plastic laminate, variable dimensions

Beverly (Ettore Sottsass, 1981). Wood covered with plastic laminate and natural briar, two-door container with shelf, 175 x 48 x 228 cm

Carlton (Ettore Sottsass, 1981). Manufacturer wood, plastic laminate, 190 x 40 x 196 cm

Lido (Michele de Lucchi, 1984). Wood, plastic laminate, metal, woollen or cotton fabric, 150 x 95 x 90 cm

Tawaraya – Boxing Ring (Masanori Umeda, 1981)

Vanity (Hans Hollein, 1982).

Very energetic blog, I enjoyed that a lot. Perhaps there is a part 2? fdedkkdfeecc